Forty years after the deadly Union Carbide gas leak, Bhopal's surrounding areas have developed with residential and commercial growth, but lingering contamination and slow industrialization continue to haunt the city.

Forty years after the catastrophic gas leak at the Union Carbide factory, which claimed over 5,400 lives and injured more than half a million people, Bhopal’s once-neglected outskirts are now home to a growing number of residential colonies and commercial establishments. However, despite the urban expansion, the legacy of the disaster lingers in the form of toxic contamination, raising concerns about development in the area.

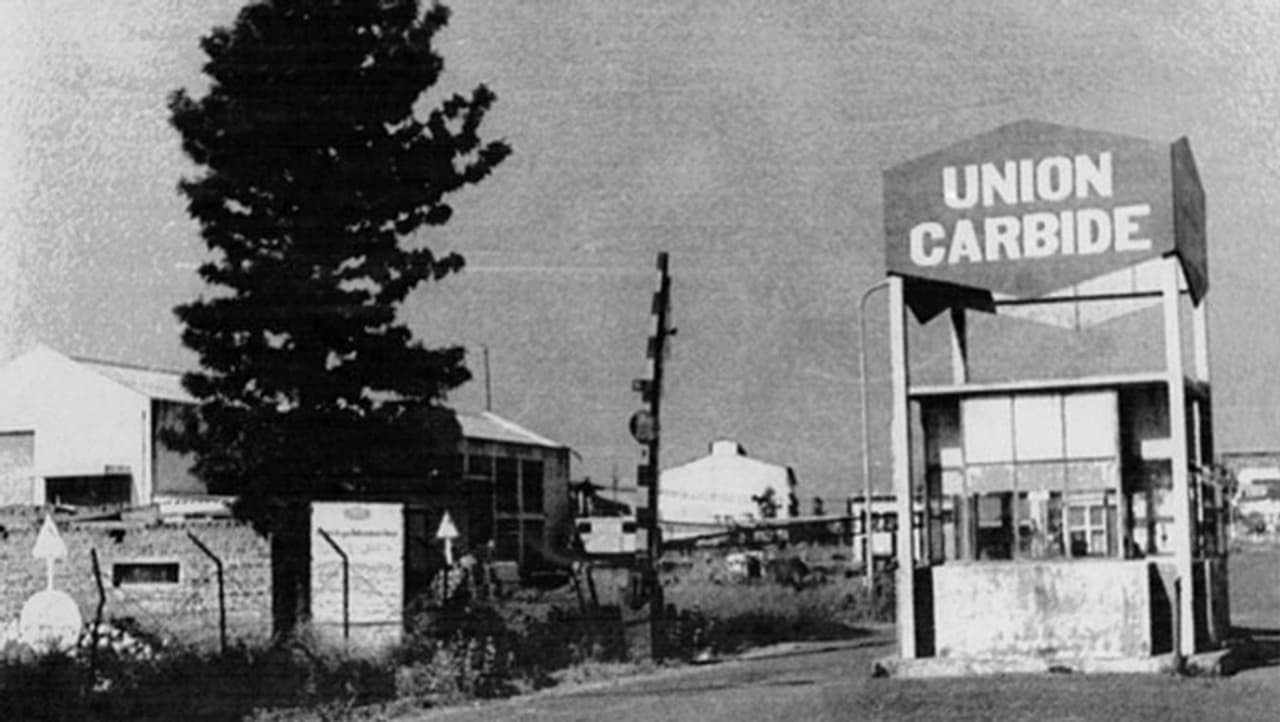

The Union Carbide plant, which was located on the fringes of the city at the time of the disaster in 1984, is now surrounded by residential colonies, shopping malls, and entertainment centers, some of which are only about 4 kilometers away from the infamous site. The highly toxic methyl isocyanate gas leak, which occurred during the night of December 2-3, 1984, remains one of the deadliest industrial disasters in history.

Vishnu Rathore, a former corporator who represented the areas near the factory site, explained that the region has experienced a significant transformation over the past four decades. "What was once on the outskirts is now in the heart of the city," he said, noting that hundreds of new colonies and shopping outlets have sprung up, despite the area's proximity to the contaminated site.

Real estate development, though slow and often haphazard, has flourished in the years following the disaster. Manoj Singh Meek, the chief of CREDAI Bhopal, noted that the northern part of the city, including the vicinity of the Union Carbide plant, has seen the addition of around 100 residential colonies and an influx of approximately 300,000 people.

However, Meek emphasized that the disaster has had long-lasting effects on Bhopal’s growth. "The city lagged behind other state capitals in industrial and business development due to the tragedy," he said, pointing out that Bhopal's economic growth slowed, and large-scale industrial projects were few and far between.

At the time of the disaster, Bhopal's population was approximately 8.5 lakh. The immediate aftermath saw many people leave the city due to health concerns and fears of persistent contamination. But over time, the population grew again, as the city saw urbanization and increased economic opportunities. By 1991, the population had begun to stabilize, even as many areas surrounding the disaster site remained underdeveloped.

While the real estate boom in the peripheral areas has been significant, the land directly adjacent to the Union Carbide site has seen more cautious development. The site itself remains largely abandoned, with little commercial or residential construction taking place nearby due to concerns about contamination.

Shubhashis Banerjee, former chairman of the Institute of Town Planners India, MP Chapter, stated that much of the development in the area has been illegal. "The compensation distributed after the tragedy spurred small-scale illegal real estate projects," he said, stressing that the catastrophe site was not handled adequately, unlike other sites of major disasters globally. Banerjee also criticized the lack of a proper memorial, which he believes could have been a significant development opportunity.

The real estate boom was also fueled by infrastructure projects, including the construction of an overbridge parallel to the Union Carbide campus. However, according to Rachna Dhingra of the Bhopal Group for Information and Action, these developments have come at a cost. "Large-scale real estate projects took off after the overbridge was constructed on the solar evaporation ponds, which were used to dump toxic waste," she said, adding that parts of the ponds have been encroached upon.

While the area continues to see development, concerns about lingering environmental contamination persist. Despite some efforts by the government, such as a 2010 proposal to relocate settlements near the disaster site, the situation remains precarious. Dhingra pointed out that the toxic soil and groundwater continue to pose a serious threat to residents, a situation she attributes to the negligence of local politicians.

As Bhopal grows and transforms, the shadow of the Union Carbide disaster continues to cast a long, toxic footprint over the city’s development. The lessons from this dark chapter of the city’s history, however, appear to have slowed down industrial progress, leaving Bhopal in a complex state of urban expansion marred by environmental and health risks.