Writer Chetan Bhagat had talked animatedly about the hot round phulka about four years ago in a column he had written to espouse the cause of the working Indian wife in general and his own in particular. The column had sparked a polarised debate that had lasted months. Bhagat had famously said his wife – the COO of an international bank – did not make phulkas at home and he was okay with that.

He also happened to say that “But the modern age that we are in, the phulka-making bride may come at a cost of missing out on other qualities.” What other qualities? – the nation’s women wanted to know. Do you think housewives are not educated? - they trolled him mercilessly. Bhagat may have been well-meaning, but his inability to understand that a wife would want to work and still make the phulka at home did him in, I think. It didn’t have to be one or the other.

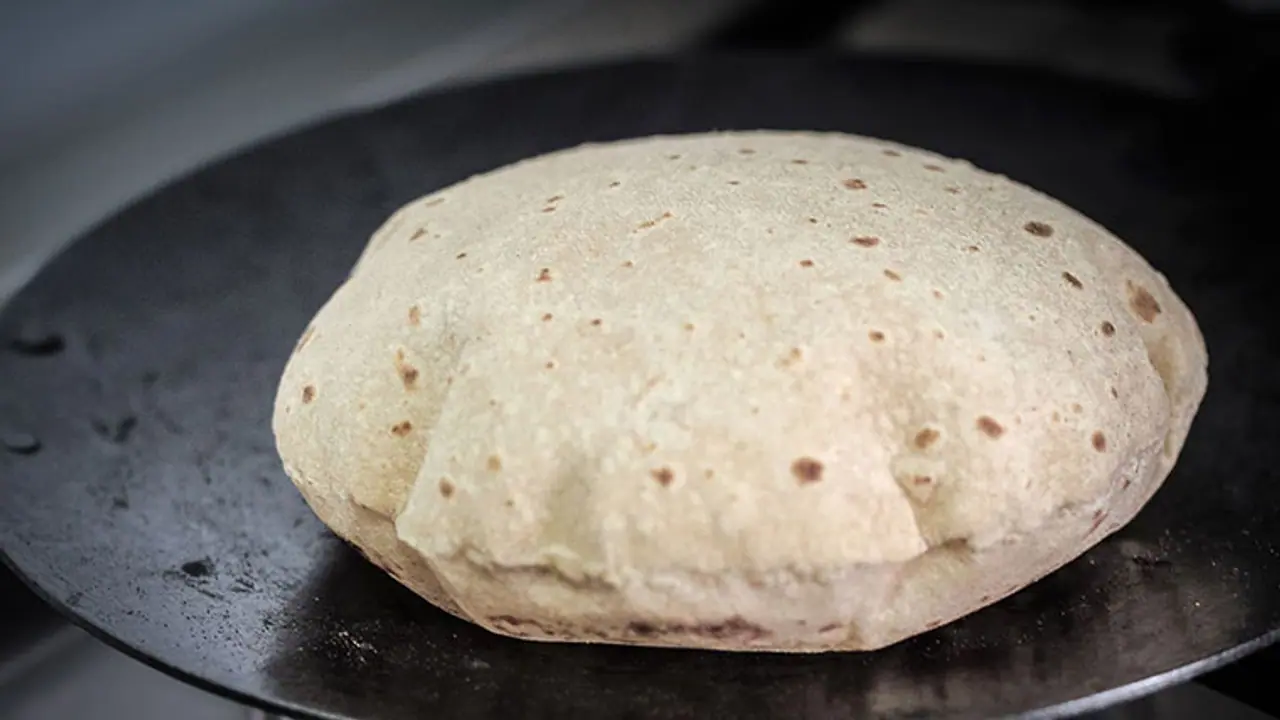

Now, the phulka. It has gained undeserved notoriety as a symbol of women’s oppression. The woman furiously rolling out hot rotis in a sweaty, smoky kitchen while the man enjoys his cup of tea and newspaper/TV is a hard collective imagery to live down. The chakla-belan is often an insult of a phrase dished out to show women “their place”. And then there’s the stress on the roundness.

Most Indian girls, until the last generation at least, were terrorised with the prospect that their phulka s , their primary KRA at their adult households, would not be perfect circles and bring all-round disappointment.

In the film, Bend It Like Beckham, the angry Mrs Bhamra admonishes, “What family would want a daughter-in-law who can run around kicking football all day but can’t make round chapattis?” She was impressing on her footballer daughter Jess that if round was the shape she wanted most in her life, it better be the wholesomeness of the chapatti, not the football. Most Indian girls, until the last generation at least, were terrorised with the prospect that their phulkas, their primary KRA at their adult households, would not be perfect circles and bring all-round disappointment.

And thus the phulka became more than just what it is, India’s favourite staple side with the curry or the bowl of dal. Feminist debate aside, what makes the chapatti round? What’s wrong with eating a square roti? Or rolling out one that looks like Africa, as most first-timers manage to?

The corners. For a roti to transcend itself into a hot steam-filled ball of a phulka on the stove, it has to be, not just round, but even. A combination of factors contributes to that. The dough has to be perfectly mixed. The tawa has to be perfectly heated. The rolling pin (aka the belan) has to be just the right shape. And then there’s skill, acquired skill that comes with hours of practice that will help you bring it around. Men and women can both try their hand at it. It is equally difficult for either sex. Well, maybe a little more for the women with centuries of performance pressure staring down at them.

I do roll my eyes at them, but you may want to reconsider giving it up to the comfort of the instant roti-makers. Trust me, a hand-rolled phulka will bring your culinary skills full-circle.

The Hack

- When you’re rolling the roti out, dip the pressed ball in loose flour on both sides, place it on the surface, and roll out the first stroke. You will get a small oval.

- Now turn the oval you have created so that it faces you horizontally. Now the fun starts. Start rolling the oval out, pressing a little more on one side than the other. Go on doing that until you have covered the entire border of the oval. It should be almost round by now. If it isn’t, roll out the bits that’ll make it round. Rub the surface with a little flour if you need to.

- Make sure it doesn’t go too thin or too thick anywhere. Smoothen it out if it does. Yes, a round phulka is a work of a few artistic touches here and there. It doesn’t happen in one go, mostly.

Image source: