Amid a devastating earthquake that rocked Nepal and Northern Bihar in 1934, a British officer spotted Mithila art while inspecting the ruins. Mesmerised by the beauty in the chaos, he decided to take the art form to the world.

In the aftermath of a devastating earthquake that rocked Nepal and Northern Bihar in 1934, a British officer spotted Mithila art while inspecting the ruins. Mesmerised by the beauty in the chaos, he decided to take the art form to the world.

A British civil servant William Archer had stumbled upon a breathtaking visual tapestry adorning the walls of crumbling homes. Little did he know, this moment would later mark the global awakening to the ancient and evocative Mithila art, widely known today as Madhubani painting.

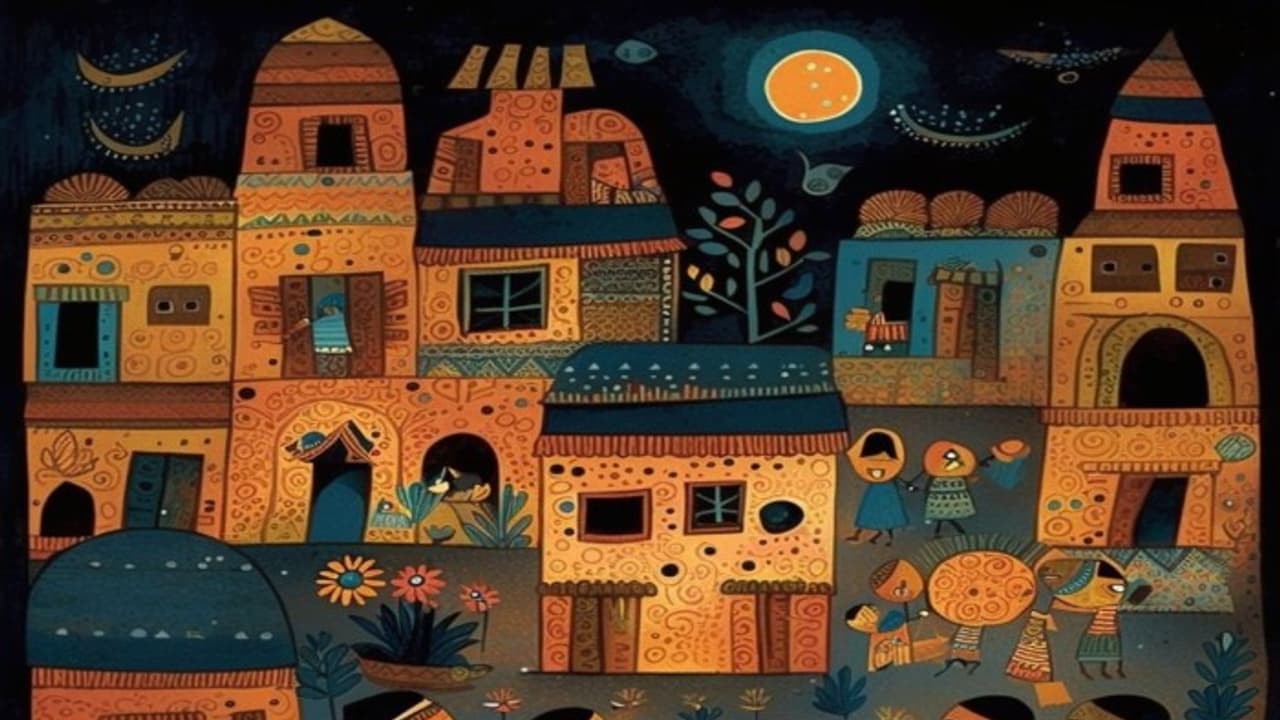

Decades later, in a quiet village in Bihar, clusters of women still gather with precision and purpose around city walls, dipping brushes into vivid pigments. Against the ochre backdrop of mud walls, they trace ancestral tales with unflinching hands. The artwork unfolds like a visual epic — a symphony of color and symbolism that narrates centuries of tradition in bold, tribal motifs.

These paintings, known as Mithila art, are no longer confined to rural courtyards. They now grace galleries, elite drawing rooms, and institutions around the world. Yet, the unlikely catalyst for this global rise was tragedy — an earthquake and the discerning eye of a colonial officer who recognized beauty where most saw only wreckage.

Beauty in the ruins

On that fateful day in 1934, as tremors shattered buildings, William Archer began his tour of the affected villages. Amidst the broken walls and crumbling temples, he stumbled across a sight that, in his own words, “took my breath away.”

“I had ridden out one evening to a village close to Madhubani itself and chanced upon a small white temple. The mahant (priest) invited me to see the image. It was a black stone dressed in doll-like clothes. The houses had been severely damaged yet not so damaged that none were standing. I could see beyond the courtyards into some of the inner rooms; what I saw took my breath away.”

Archer had discovered a kobhar — a marriage chamber painted with intricate murals to bless the union of bride and groom with fertility and fortune.

“What I was seeing was a marriage chamber, a kobhar. It was here that the bride and bridegroom would be espoused and everything painted was designed to bring them prosperity, good fortune and fertility.”

The deeper he delved, the more he was enchanted by the striking variations across households, shaped by caste, region, and lineage.

“The style of their murals was quite distinct. It presupposed the same liberties, the same repudiation of truth to natural appearances, and the same determination to project a forceful idea of a subject rather than a factual record. But in contrast to Brahmins, Kayastha women were vehement — they portrayed their main subject with shrill boldness, with savage forcefulness.”

“I must confess that for at least an hour, I forgot the earthquake and its horrors. I was entranced by what I saw in these murals we somehow electrically met. What they took for granted, I considered superb…the art was there and made us one…I saw the beauty in the mud.”

Mithila’s ascent to the world stage

Though Archer published a paper in 1949 chronicling his discovery, the art form remained relatively obscure. Determined to give it the platform it deserved, Archer reached out in 1966 to Pupul Jayakar, head of the All India Handloom Board. Jayakar, equally moved by the art’s rustic power, enlisted artist Bhaskar Kulkarni. Together, they set about training the women of Jitwarpur and Ranti to transfer their mud-wall art onto paper.

This shift was revolutionary. In 1967, the first gallery of Mithila paintings debuted in New Delhi. By 1970, these vividly painted narratives had captivated audiences in Japan, Europe, the USSR, and the United States.

The art of Mithila had officially transcended borders.

German anthropologist Erika Moser, French filmmaker Yves Vequaud, and American academic Raymond Owens helped popularize the artwork in the West — buying paintings, showcasing them abroad, and channeling profits back to their creators in Bihar.

What is it about Mithila art that so captivates the soul?

Its origin, as believed, dates back to the 7th century BCE, when King Janak is said to have commissioned these paintings for the wedding of his daughter Sita to Lord Rama.

The paintings are a visual celebration of mythology, nature, and geometry. Sun and moon motifs, peacocks and fish, deities and lotus blooms—every element is richly symbolic. Colors are derived from nature: black from cow dung, red from sandalwood, yellow from turmeric, and blue from indigo. Not a sliver of canvas is left unfilled — every inch tells a story.

And today, as the women of Bihar hunch over walls or sheets of handmade paper, brushing life into their lines, they do more than paint. They preserve heritage. They whisper history. They celebrate resilience.