Lord Mayo launched India’s first full census in 1871–72, aiming to govern better by counting caste, religion, and occupation. His assassination in 1872 marked a dramatic end to a Viceroy's push for data-driven rule.

As India gears up for its next national census—delayed since 2021—the debate over including caste data has reignited long-standing questions about identity, governance, and social justice.

The Union Cabinet has announced that caste enumeration will be part of the forthcoming population count, marking a potential turning point in how the state understands and engages with its citizens.

Political parties are sharply divided on the move. While the Opposition sees it as a long-overdue corrective to structural inequities, the ruling BJP argues it will strengthen targeted welfare and national planning.

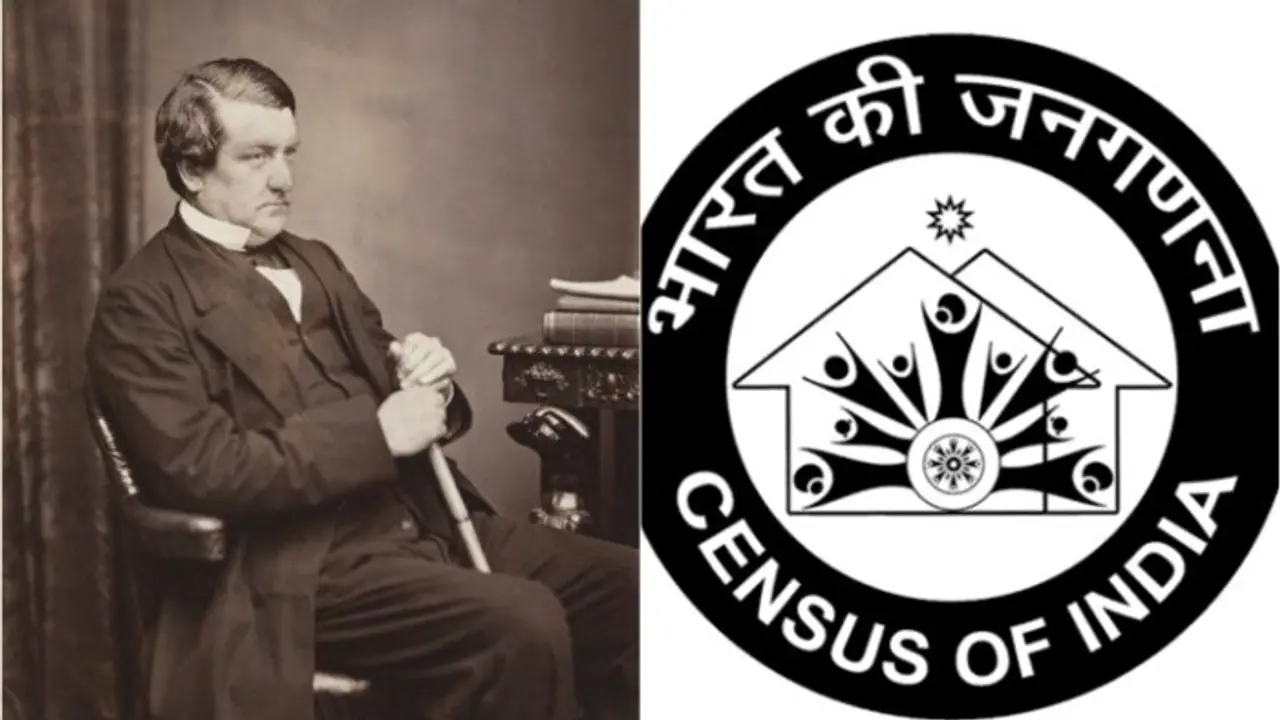

But this isn’t the first time India has wrestled with the complexities of counting its people. The origins of this mammoth exercise go back more than 150 years—to a man whose administrative vision and tragic end remain entwined with India’s census legacy: Richard Bourke, better known as the 6th Earl of Mayo and the only Viceroy of India to be assassinated in office.

A census born in colonial anxiety

On February 8, 1872, Lord Mayo was fatally stabbed by a convict during an inspection at the Andaman Islands’ penal colony. But his greater legacy lives in the structures of modern Indian governance. Under Mayo’s leadership, British India launched its first pan-subcontinental attempt to count its population—a bold bureaucratic project rooted in both imperial curiosity and post-1857 administrative insecurity.

In the wake of the 1857 rebellion, British policy shifted from indirect rule via the East India Company to direct governance by the Crown. For administrators in London and Calcutta, knowledge was power. Mayo championed the idea that effective control of such a vast and diverse land demanded comprehensive data—about land, caste, religion, occupation, and demography.

In 1869, Mayo commissioned the Statistical Survey of India under William Wilson Hunter. More importantly, he authorised the 1871–72 Census—the first time a systematic enumeration of India’s entire population was attempted under a common methodology. This census covered both British provinces and princely states and involved over half a million enumerators, a feat unprecedented in scale at the time.

Fixing caste, shaping rule

While previous local counts existed—such as in the Bombay Presidency in 1827—the 1871–72 census introduced a new level of detail and bureaucratic ambition. It aimed to categorise Indians by caste, religion, language, occupation, age, and literacy—categories that continue to define modern censuses.

The colonial state’s interest in caste and religion went beyond administrative convenience. British ethnographers and officials sought to fix India’s social structure in ways that served imperial governance, often reducing fluid and dynamic identities into rigid hierarchies. Caste, once a complex web of regional and occupational affiliations, began to be frozen into typologies that persist even today.

Lord Mayo justified the exercise as an imperial necessity. “You cannot govern men unless you know them,” he famously said. But in the act of “knowing,” the British administration also began to define and divide—an approach many scholars believe sowed the seeds for modern caste and communal identities.

The price of counting

Mayo’s assassination in Port Blair added a dramatic and mysterious twist to his legacy. His killer, Sher Ali Afridi, was a Pashtun convict who had once served in the British Indian Army. While Sher Ali insisted he acted alone to avenge Muslim grievances, colonial officials were left rattled. Some speculated whether the reforms and interventions under Mayo—particularly his push for statistical scrutiny of society—had triggered deeper unrest.

Although no direct link was ever found between the census and Mayo’s murder, resistance to enumeration was very real. In several regions, villagers refused to give information, fearing taxation, land seizure, or conscription. In some cases, families hid women or children from enumerators. In others, caste leaders protested the process itself, wary of how it might undermine their influence.

The shadow of Mayo’s census

Despite its flaws, the 1871–72 count estimated India’s population at roughly 255 million and set the template for what would become one of the world’s largest administrative exercises. Today, the Census of India employs over 3 million enumerators and collects data on dozens of parameters.

Yet the colonial fingerprints remain. The legacy of fixed categories—especially in caste—continues to shape political debates, social policies, and identity struggles. As India prepares to revisit caste enumeration in its next census, echoes of Mayo’s era are unmistakable: Who gets counted, how, and why remain fiercely contested.

On the morning of February 8, 1872, Lord Richard Bourke set off on what was meant to be a routine inspection tour to the penal colony on the Andaman Islands. He was stabbed by a convict named Sher Ali, becoming the only Viceroy of India ever to be assassinated in office.

But Lord Mayo's legacy extends far beyond the tragedy of that day. It was during his tenure that India undertook its first-ever comprehensive effort to count its people—a project that would evolve into the decennial Census of India. More than a bureaucratic exercise, that first enumeration revealed the colonial anxieties, ambitions, and contradictions that would shape governance for decades to come.

Lord Mayo’s life ended on a remote island with a knife to the chest. But the system he created endures—defining how India knows itself, governs itself, and argues with itself. As the country braces for a historic population count with caste back on the ledger, the story of the first census reminds us that data is never neutral. It is always a reflection of power, purpose, and politics.