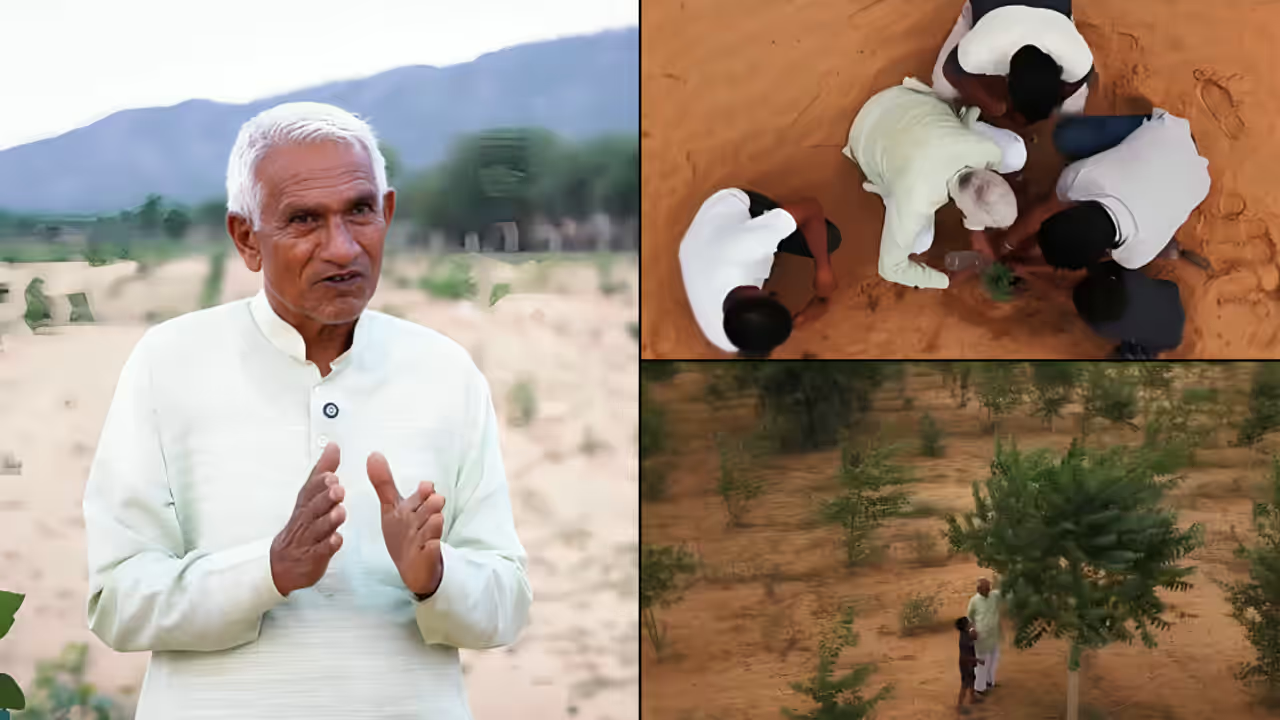

Sundaram Verma, a Padma Shri farmer from Rajasthan, has grown over 60,000 trees using just one litre of water per plant. By trapping monsoon moisture through deep ploughing, his method saves water and helps trees survive drought.

In a region where water disappears faster than hope, one farmer has quietly proved that even the harshest land can grow green again. In the dry village of Daanta in Rajasthan's Sikar district, Sundaram Verma bends near a young sapling and presses the soil gently around its roots. He smiles, satisfied. The tree is healthy. Like more than 60,000 others he has planted, it has survived on just one litre of water.

In Rajasthan, where water scarcity is a daily struggle and rainfall is brief and uncertain, this sounds almost impossible. But for Sundaram Verma, it has been a life’s mission, shaped by the land he grew up on, refined through decades of trial, and shared freely with farmers across India.

Today, Sundaram is a Padma Shri awardee. Yet he still introduces himself simply as a farmer.

Growing up with dry land and hard work

Sundaram Verma was born in 1950 in Daanta village, at a time when India was newly independent and Rajasthan was already battling water shortage. Life was simple, tough, and deeply tied to farming.

“When I took admission in Class One, I would go straight to the farm after school,” he tells The Better India. “That was just how life was back then.”

His father Ishwarlaal, his uncle Gangaram, and his grandfather Lakshminarayan Verma all worked on the land. Farming was not a choice, it was the family’s identity.

Water was always limited. Crops depended fully on the monsoon. If the rains failed, so did the harvest. These early experiences shaped Sundaram’s understanding of soil, seasons, and survival.

But one event changed how he looked at life beyond the fields.

The uncle who changed the family's future

In Sundaram’s family, one younger uncle, Tulsiram, was allowed to study instead of working full-time on the farm. In 1957, he passed Class 10 and became a school teacher, the first educated person in the family.

“That was a turning point for us,” Sundaram says. “For the first time, we saw education as a tool that could change lives.”

Watching his uncle succeed left a deep mark on him. Sundaram realised that learning and farming did not have to be separate. Knowledge could strengthen agriculture, not replace it.

From that moment, he decided to study, observe, and experiment, not in classrooms alone, but in the fields.

The breakthrough came in 1985. During routine monsoon ploughing, Sundaram noticed something unusual. A sapling planted earlier survived without any extra watering. It had grown only on rainwater stored in the soil.

That single observation stayed with him. Over the next ten years, Sundaram began testing and refining the idea. He observed how soil absorbed water, how deep roots reached moisture, and how weeds competed with young plants.

By around 1995, he had developed a reliable system. It was simple, low-cost, and did not depend on pumps or irrigation.

Since then, for more than 30 to 35 years, Sundaram Verma has planted over 60,000 trees across Rajasthan using this method.

Farming with nature, not against it

Sundaram’s technique works by respecting the land’s natural cycle.

“We wait for the first monsoon showers and then plough the soil about 20 centimetres deep,” he explains to The Better India. “This helps the soil absorb more water and removes weeds that take up moisture.”

As the rains continue, the soil traps moisture below the surface. Just before the monsoon ends, usually in late August or early September, he ploughs again, this time deeper.

This second ploughing creates a natural moisture store beneath the ground.

“When we plant saplings with roots reaching about 25 centimetres deep, they tap into that hidden moisture,” he says. “They grow strong without extra watering.”

Each sapling receives just one litre of water at planting. After that, it survives on stored soil moisture.

This method has helped save more than nine lakh litres of water over the years.

Sixty thousand trees and counting

What started as a local experiment slowly turned into a proven system.

Sundaram has planted more than 60,000 trees across Rajasthan, in sandy soil, extreme heat and low rainfall zones. These trees include native species suited to dry climates.

The success drew attention from farmers facing falling groundwater levels and unpredictable rains. Many came to see his fields with their own eyes.

They saw green patches where dry land once dominated.

Over time, Sundaram’s one-litre method spread quietly, farmer to farmer, village to village.

Recognition without leaving the fields

In 2019, Sundaram Verma received the Padma Shri, one of India’s highest civilian honours. The award recognised his lifelong work in water conservation and sustainable farming.

A year later, in 2020, Mahatma Jyoti Rao Phule University awarded him a PhD for his field-based contributions to agriculture.

Despite national recognition, Sundaram’s daily routine did not change much. He still spends most of his time on the farm, observing, teaching and experimenting.

A family effort rooted in shared values

Sundaram's work is not a solo journey. It is deeply supported by his family. His wife, Bhagwati Devi, now 73, works alongside him with equal dedication. She has developed two techniques for termite control, both of which have received national awards.

“She manages the home and works in the fields with incredible energy,” Sundaram tells The Better India with pride.

Their two sons and daughters-in-law work full-time on the farm. His five daughters are married and settled, but remain closely connected.

His daughters-in-law help label, monitor and manage seed experiments. Seed preservation, record-keeping, and testing are shared responsibilities.

"This is not just farming," Sundaram says. "It is teamwork."

Alongside tree planting, Sundaram has focused heavily on seed conservation. Over the years, he has preserved more than 700 seed varieties from 15 major crops, including both kharif and rabi varieties native to Rajasthan’s dry regions.

These seeds are climate-resilient and adapted to low water conditions. His aim is clear: help farmers move back to native crops that need less water and survive extreme weather.

In line with government efforts to revive indigenous agriculture, Sundaram now develops improved native seeds and distributes them freely to farmers.

Teaching farmers to save water and income

Since 2020, Sundaram has expanded his outreach beyond his village. He trains farmers across Rajasthan and other states in what he calls the '1 Rupee per Litre Water' technique. The name reflects how affordable and accessible the method is.

“I want to help people increase income while saving water,” he explains. “Water conservation is no longer optional.”

Farmers visit his farm to learn directly, watching, asking questions, and practising the method themselves.

Ramesh Meena, a young farmer from Jhunjhunu, is one of many who benefited. “Before I met Sundaram ji, I thought farming in dry regions meant constant failure,” he says. “After training with him, I planted over 200 trees using his method. They are thriving.”

For Ramesh, the lesson went beyond technique. “He didn’t just teach farming. He taught us to believe that change is possible.”

Sundaram is also a long-time member of the Honey Bee Network. Through it, he documents and shares grassroots innovations with NIF India. “I continuously compile and share knowledge so it reaches others,” he says.

For him, ideas only matter when they are shared.

Today, Sundaram focuses on growing millets, mustard, and cotton with minimal water. Climate change, he believes, makes conservation urgent. “Rain patterns are changing. Groundwater is falling,” he says. “We must prepare.” Yet he does not speak in grand terms. He prefers action over speeches.

He keeps planting trees. Keeps training farmers. Keeps trusting the soil.

Sundaram Verma does not call his work a movement. He simply does what he has always done. In a world of shrinking water resources and rising uncertainty, his life offers a quiet lesson: solutions do not have to be complex.

Sometimes, all it takes is one litre of water, used with care