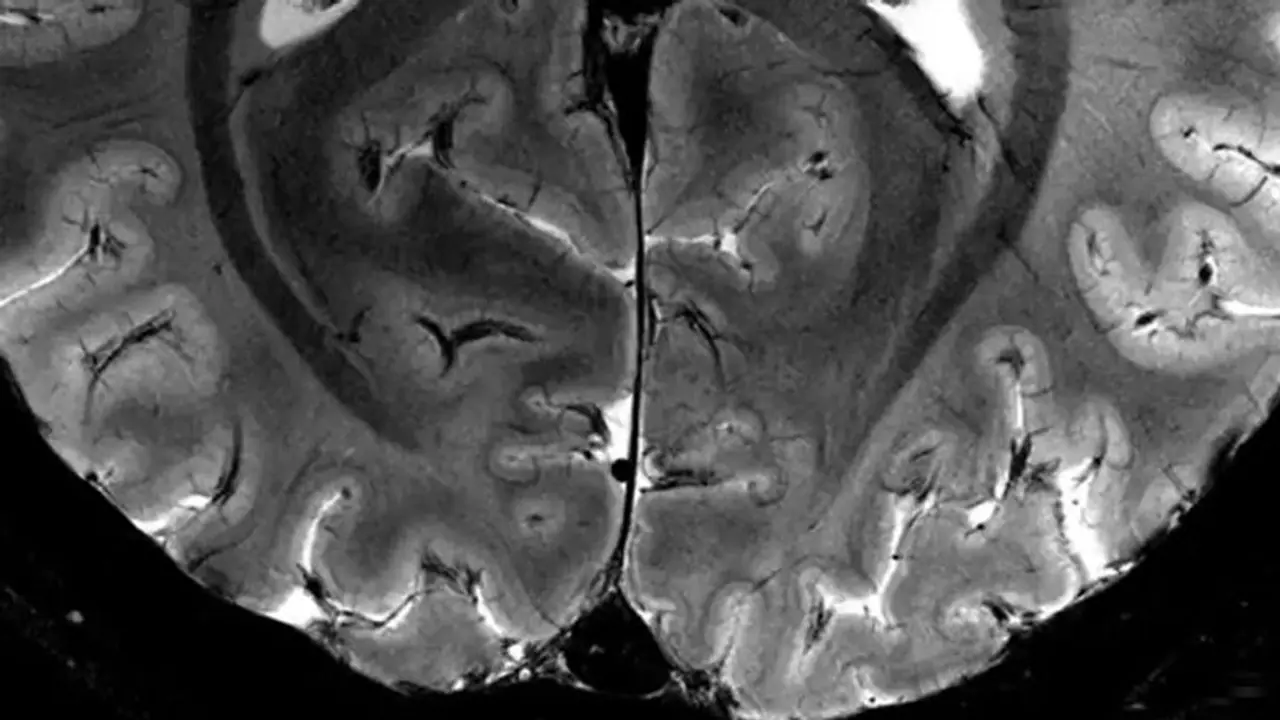

The world's most powerful MRI scanner has generated its inaugural images of human brains, achieving an unprecedented level of precision poised to illuminate the enigmatic workings of our minds and the ailments that afflict them.

The world's most powerful MRI scanner has generated its inaugural images of human brains, achieving an unprecedented level of precision poised to illuminate the enigmatic workings of our minds and the ailments that afflict them. Researchers at France's Atomic Energy Commission (CEA) initially utilized the machine to scan a pumpkin back in 2021. However, health authorities have recently granted approval for human scans.

Over the past several months, approximately 20 healthy volunteers have ventured into the magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) machine, situated in the Plateau de Saclay region south of Paris—an area teeming with technology firms and academic institutions.

"We have seen a level of precision never reached before at CEA," said Alexandre Vignaud, a physicist working on the project.

The scanner's magnetic field, measuring a staggering 11.7 teslas, is named after inventor Nikola Tesla, marking a significant leap in scanning capability. This level of power enables the machine to produce images with tenfold precision compared to the MRIs typically found in hospitals, which typically operate at three teslas or less.

Vignaud compared images captured by the formidable scanner, dubbed Iseult, with those obtained from a standard MRI, highlighting the remarkable difference in clarity and detail.

"With this machine, we can see the tiny vessels which feed the cerebral cortex, or details of the cerebellum which were almost invisible until now," he added.

France's research minister Sylvie Retailleau, herself a physicist, expressed astonishment, stating, "the precision is hardly believable!" In a statement to AFP, she emphasized that this groundbreaking achievement will "allow better detection and treatment for pathologies of the brain."

All about world's most powerful MRI scanner

The machine, contained within a five-meter (16-foot) long and tall cylinder, houses a 132-tonne magnet powered by a coil carrying a current of 1,500 amps. With a 90-centimeter (three-foot) opening for humans to slide into, the design represents the culmination of two decades of collaborative research between French and German engineers.

The United States and South Korea are collaborating on the development of similarly powerful MRI machines, although they have not yet commenced scanning images of humans.

One of the primary objectives of deploying such high-powered scanners is to enhance our comprehension of the brain's anatomy and the specific regions activated during various tasks.

Researchers have already utilized MRIs to demonstrate that when the brain processes specific stimuli—such as faces, locations, or words—distinct areas of the cerebral cortex become active.

Nicolas Boulant, the project's scientific director, noted that harnessing the power of 11.7 teslas will enable Iseult to "better understand the relationship between the brain's structure and cognitive functions, for example when we read a book or carry out a mental calculation."

The researchers aspire that the scanner's potency could also illuminate the enigmatic mechanisms underlying neurodegenerative diseases such as Parkinson's or Alzheimer's, as well as psychological conditions like depression or schizophrenia.

"For example, we know that a particular area of the brain -- the hippocampus -- is implicated in Alzheimer's disease, so we hope to be able to find out how the cells work in this part of the cerebral cortex," said CEA researcher Anne-Isabelle Etienvre.

Additionally, the scientists aim to chart how specific drugs utilized in treating bipolar disorder, such as lithium, disperse throughout the brain.

The robust magnetic field generated by the MRI will provide a more precise image of the brain regions affected by lithium. This may aid in determining which patients will exhibit better or poorer responses to the medication.

"If we can better understand these very harmful diseases, we should be able to diagnose them earlier -- and therefore treat them better," Etienvre said.

For the foreseeable future, ordinary patients won't have access to Iseult's impressive capabilities to peer into their own brains.

Boulant said the machine "is not intended to become a clinical diagnostic tool, but we hope the knowledge learned can then be used in hospitals".

In the upcoming months, a fresh cohort of healthy participants will be enlisted for brain scans.

It will take several years before the machine is utilized for patients with medical conditions.