For more than a century, the 'Curse of the Pharaohs' has intrigued many, particularly linked to King Tutankhamun's tomb discovery in 1922 by Howard Carter. It was believed to cause the deaths of over 20 connected to the excavation.

For more than a century, the 'Curse of the Pharaohs' has intrigued many, particularly linked to King Tutankhamun's tomb discovery in 1922. A recent revelation challenges the long-standing mystery surrounding the deaths of over 20 individuals associated with the opening of King Tutankhamun's tomb. While ancient Egyptian texts ominously warned of "death by a disease that no doctor can diagnose" for those disturbing royal mummified remains, Ross Fellowes proposes a biological explanation behind these fatalities.

Fellowes' study identifies radiation poisoning as the culprit, stemming from natural elements rich in uranium and deliberate placement of toxic waste within the sealed vault.

Exposure to certain substances likely contributed to specific cancers, such as the type that claimed the life of archaeologist Howard Carter, who was the first to enter Tutankhamun's tomb over a century ago.

This theory effectively confirms that the tomb was indeed 'cursed,' albeit in a deliberate, biological manner, rather than the supernatural interpretation previously suggested by some Ancient Egyptologists.

Howard Carter, who passed away in 1939, likely succumbed to a heart attack following a prolonged battle with Hodgkin's lymphoma, a cancer impacting the body's immune system, with radiation poisoning being a potential cause.

Lord Carnarvon, another explorer of the tomb, died from blood poisoning five months after the discovery. His death resulted from a severe mosquito bite that became infected after a razor cut.

Soon after the tomb's opening, a brief power outage plunged Cairo into darkness.

Carnarvon's son reported that his beloved dog howled and suddenly died.

Various individuals involved in the excavation met untimely deaths from causes including asphyxia, stroke, diabetes, heart failure, pneumonia, poisoning, malaria, and X-ray exposure, all passing away in their 50s.

British Egyptologist Arthur Weigall, present at the tomb's opening, faced accusations of propagating the 'curse' myth. He passed away from cancer at the age of 54.

Inscriptions discovered inside various burial sites across Egypt indicate that ancient people were aware of the presence of toxins. Some areas were labeled 'forbidden' due to the presence of 'evil spirits.'

A study published in the Journal of Scientific Exploration elaborated on the documentation of high radiation levels in ruins of Old Kingdom tombs, particularly in two locations at Giza and several underground tombs at Saqqara. Similar findings were observed in the Osiris tomb at Giza.

Ross Fellowes highlighted that "intense radioactivity was associated with two stone coffers, especially from the interiors."

Professor Robert Temple noted that these coffers, made of basalt, were significant sources of radiation, distinct from the general trace natural levels of radon from the surrounding limestone bedrock.

Other studies directly measured radon gas at various tomb locations in Saqqara. Radon gas, an intermediate product of uranium decay with a half-life of 3.8 days, was identified at six locations within the Saqqara ruins, including the South Tomb, Djoser’s pyramid magazines, and the Serapeum tomb tunnels.

"Reported strong radiation (as radon) in tomb ruins has been loosely attributed to the natural background from the parent bedrock. However, the levels are unusually high and localized, which is not consistent with the characteristics of the limestone bedrock but implies some other unnatural source(s)," Fellows shared.

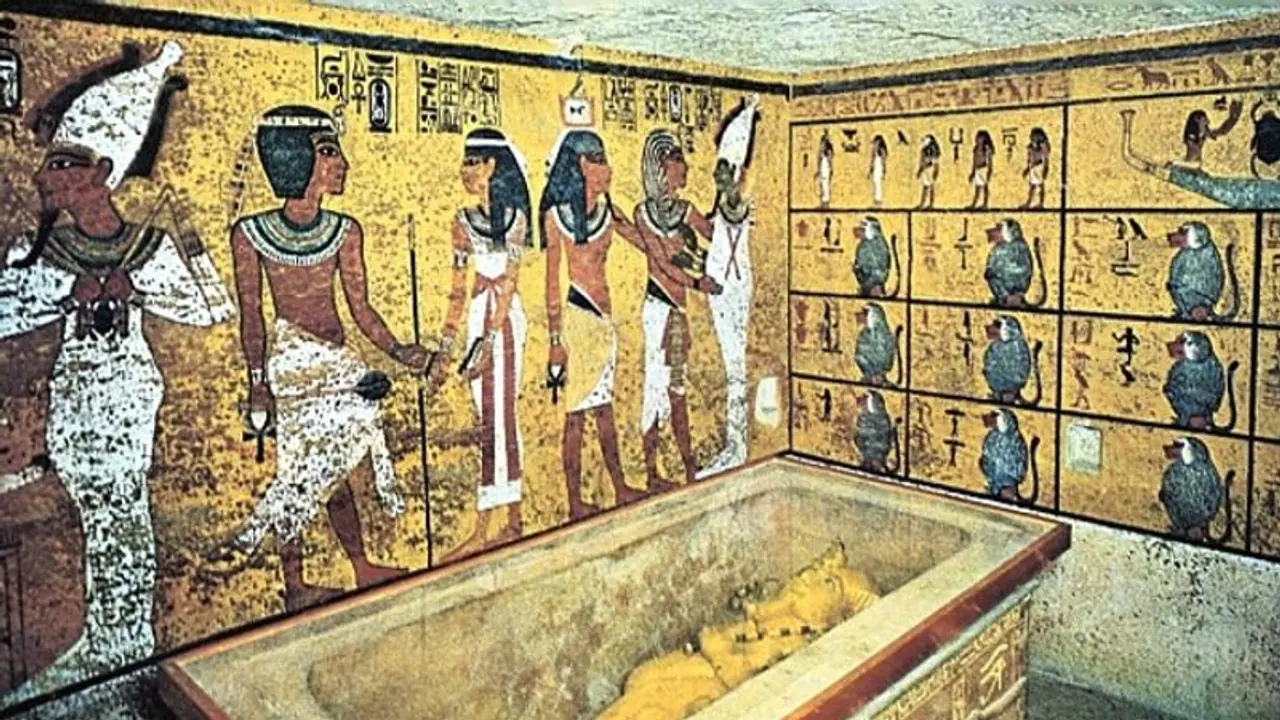

On November 4, 1922, Carter's expedition uncovered steps leading to Tutankhamun's tomb, initiating several months of meticulous cataloging of the antechamber. In February of the following year, they unveiled the burial chamber, revealing the sarcophagus within.

Tutankhamun's tomb stands as one of history's most opulent discoveries, brimming with precious artifacts intended to accompany the young Pharaoh on his journey to the afterlife. Among the trove of grave goods were 5,000 items, including solid gold funeral shoes, statues, games, and exotic animals.

The modest dimensions of Tutankhamun's burial chamber, juxtaposed with his significance in Egyptian history, have long perplexed experts. Carter and his team spent a decade carefully removing treasures from the tomb.

As an Egyptian pharaoh of the 18th dynasty, Tutankhamun reigned from 1332 BC to 1323 BC, ascending the throne at just nine or ten years old. His marriage to his half-sister, Ankhesenpaaten, marked his rule, which was fraught with health challenges due to his parents' consanguineous relationship.

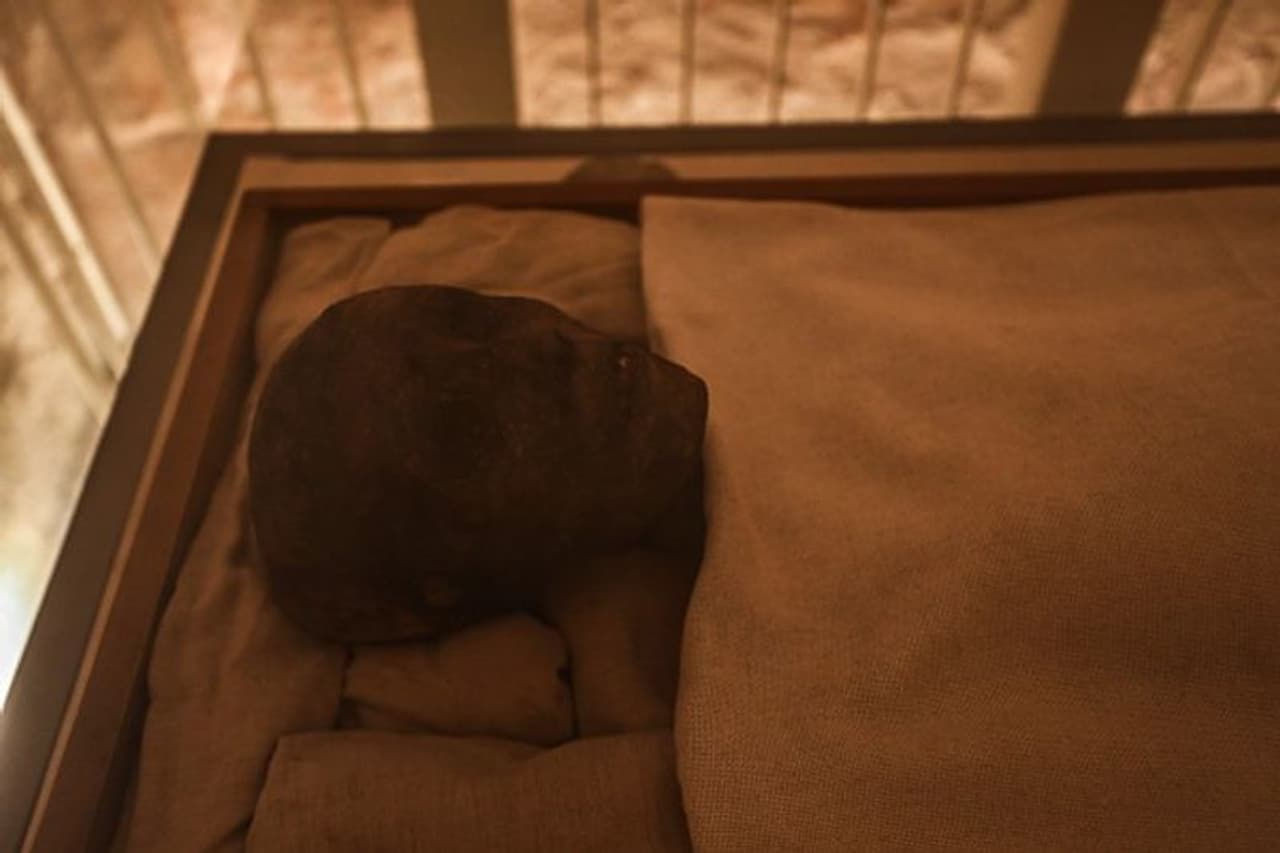

A reconstruction of Tutankhamun's face and body unveiled various ailments he likely endured, including buck teeth, a club foot, and feminine hips. Contrary to the image of a robust chariot racer often associated with ancient kings, Tutankhamun relied on walking sticks during his reign.

A 'virtual autopsy' comprising over 2,000 computer scans, coupled with genetic analysis, underscored the familial ties and hormonal imbalances contributing to Tutankhamun's physical impairments and untimely death in his late teens.

Speculations surrounding Tutankhamun's demise, once centered on murder or chariot accidents due to skeletal fractures, now lean towards inherited illnesses, supported by his club foot rendering chariot racing implausible.

Hutan Ashrafian, a surgery lecturer at Imperial College London, posited that several family members exhibited ailments attributable to hormonal imbalances, corroborating Tutankhamun's physical limitations. This hypothesis is further substantiated by the discovery of 130 used walking canes in his tomb.