When Medals Lose Their Shine: The Curious Case of Karnataka Police’s Controversial CM Awardees | Opinion

Synopsis

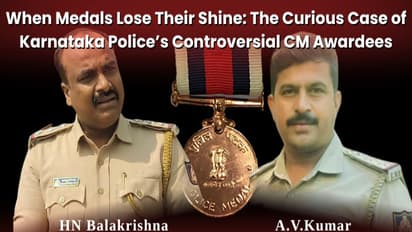

The recent controversies surrounding officers like Inspector A.V. Kumar of Annapoorneshwarinagar Police Station, Bengaluru, and Inspector H.N. Balakrishna, formerly of Ullal, paint a very disturbing picture.

In an ideal system, the Chief Minister’s Medal is meant to stand as a proud symbol of honour—recognising police officers for their bravery, integrity, and dedication to public service. But the recent controversies surrounding officers like Inspector A.V. Kumar of Annapoorneshwarinagar Police Station, Bengaluru, and Inspector H.N. Balakrishna, formerly of Ullal, paint a very disturbing picture. These medals are now being linked not with merit—but with misconduct, corruption, and systemic failure. The glaring cases of these two officers expose serious lapses in the selection process and raise a larger question: Who is being rewarded—and at what cost?

Take the case of A.V. Kumar, who was on the verge of being awarded the CM’s Gold Medal. Posted in Annapoorneshwarinagar, Kumar was all set to be honoured for his “outstanding service” until the Lokayukta swooped in with raids on the eve of the ceremony in April 2025. What came out was not just irregularities—but full-blown corruption, including illegal land dealings. According to Karnataka Home Minister G. Parameshwara, Kumar misused his official post to operate real estate deals straight from the police station—a shocking abuse of authority. And when the noose tightened, Kumar didn’t face the law—he simply vanished, leaving the medal in limbo and the department red-faced.

What makes Kumar’s case even more serious is that his rise was often backed by political figures—particularly local MLAs—and even some of his higher-ups in the department. His postings were reportedly not based on merit, but convenience and political connections, turning the police service into a playing field for vested interests.

Kumar’s case is not only embarrassing, it’s deeply troubling—especially considering he was the Assistant Investigating Officer in the high-profile Darshan case. If such a controversial officer was involved in a sensitive and high-stakes investigation, how can the public be assured that the case wasn’t compromised? His sudden disappearance only deepens the suspicion—was key evidence manipulated? Were favours traded? The government must now relook at his role in that investigation, for the sake of transparency and justice.

Then there’s Inspector H.N. Balakrishna, formerly posted at Ullal Police Station and now at Pandeshwar Women’s Police Station, Mangaluru. He is facing serious allegations of corruption. In June 2024, the mother of a youth arrested for theft in Ullal lodged a complaint with Police Commissioner Anupam Agrawal, accusing Balakrishna of misconduct. She claimed that the Inspector took 50 grams of gold ornaments from her son, stating they were related to the case and would be reflected in the chargesheet so they could be reclaimed through court. However, the ornaments were not mentioned in the chargesheet, and the family alleges that Balakrishna has kept them. Additionally, she alleged that Balakrishna took ₹3 lakh from her in June 2024 with a promise to close the case. Commissioner Agrawal has ordered Assistant Commissioner of Police Dhanya Nayak to conduct a preliminary inquiry into the allegations, and a report is awaited.

Also read: Tariff titans: India and the US face off in a high stakes trade dance | Opinion

Both these cases reflect a deeper problem: a flawed, secretive, and perhaps politically compromised selection process. The process, it seems, is driven by top-down recommendations from ACPs, DCPs, SPs, Commissioners, and even the DGP. And if a Medal Selection Committee was constituted—as is often the case—then all its members are equally responsible for not conducting proper vetting. Background checks seem to have become optional, and integrity has been pushed to the sidelines.

In Kumar’s case, political interference and strategic postings aided his rise. In Balakrishna’s case, despite fresh and ongoing allegations of serious misconduct, he continued receiving support from within the system. Are these medals truly a reward for service—or merely tools of patronage?

This is not just carelessness—it’s a betrayal of the very purpose of the medal. When dishonest officers are allowed to wear the CM’s Medal on their chest, the public loses faith, and honest officers—those who serve with true dedication—are left demoralised. The prestige of the medal, linked to the honourable office of the Chief Minister, becomes a casualty in this drama of privilege and backdoor politics. And now, with ACP Dhanya Nayak investigating Balakrishna’s case—there’s talk of her transfer, which could stall the entire inquiry. If that happens, the suspicion of a cover-up will only grow stronger.

This mess calls for urgent reforms. The system needs to be fixed—starting with complete transparency. Publish the selection criteria. Reveal the names of the recommending authorities. Let an independent civilian panel be part of the screening process. Make integrity and public perception part of the evaluation—not just case stats or departmental goodwill. And open the doors to public scrutiny—because these medals are meant to serve the people, not protect the powerful.

If this broken process continues, the CM’s Medal will become a joke—a hollow symbol, handed to those who manipulate the system instead of upholding it. The stories of Kumar and Balakrishna are not isolated—they reflect a deeper rot. Cleaning it up is not just about saving the medal’s prestige. It’s about sending a strong message that in Karnataka, honesty still matters—and corruption will not be rewarded.

Otherwise, these medals will lose their shine, reduced to mere props in a drama of power and privilege.

(The author Girish Linganna of this article is an award-winning Science Writer and a Defence, Aerospace & Political Analyst based in Bengaluru. He is also Director of ADD Engineering Components, India, Pvt. Ltd, a subsidiary of ADD Engineering GmbH, Germany. You can reach him at: girishlinganna@gmail.com)

Stay updated with the Breaking News Today and Latest News from across India and around the world. Get real-time updates, in-depth analysis, and comprehensive coverage of India News, World News, Indian Defence News, Kerala News, and Karnataka News. From politics to current affairs, follow every major story as it unfolds. Download the Asianet News Official App from the Android Play Store and iPhone App Store for accurate and timely news updates anytime, anywhere.