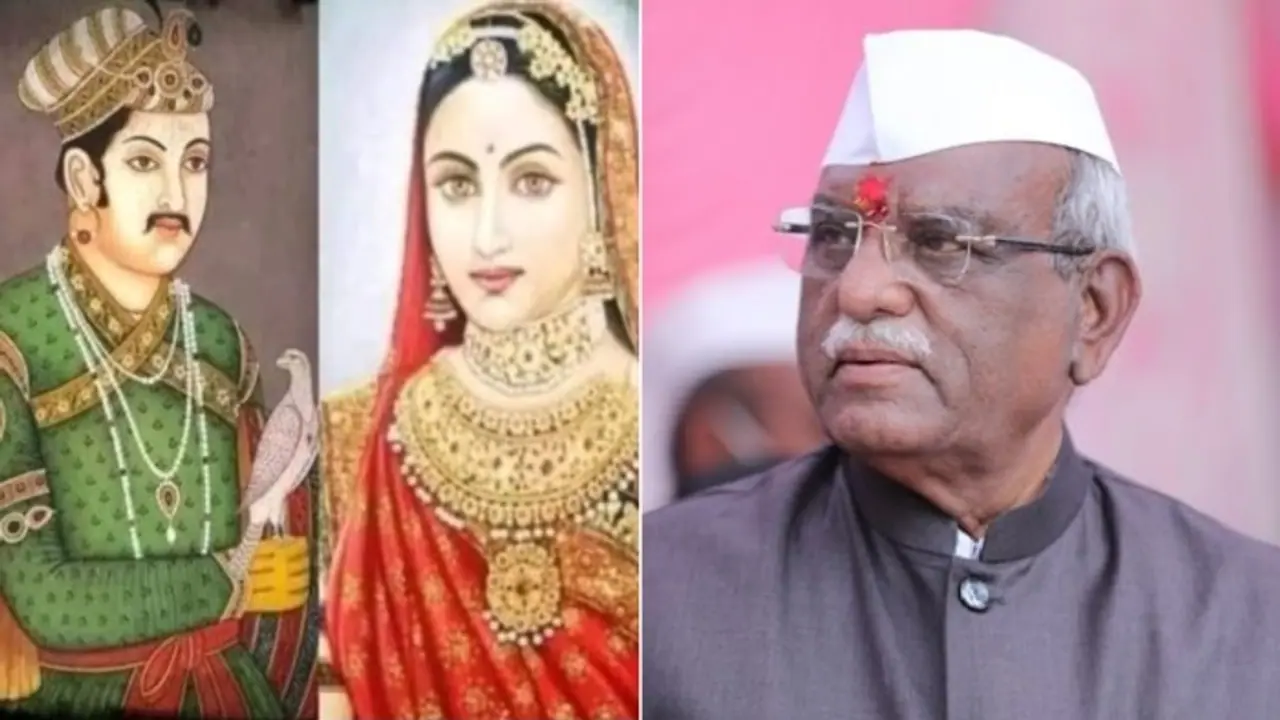

Governor Haribhau Bagde has challenged the popular narrative of Mughal emperor Akbar marrying Rajput princess Jodha Bai, calling it a historical distortion by British historians and urging a relook at India's rewritten past.

Rajasthan Governor Haribhau Bagde stirred up a major historical controversy this week by claiming that Mughal emperor Akbar did not marry a Rajput princess, as widely believed, but the daughter of a palace maid from Amer.

Speaking on Wednesday evening at the Pratap Gaurav Kendra in Udaipur, ahead of Maharana Pratap's birth anniversary, Bagde questioned one of Indian history’s most well-known royal alliances and accused British historians of reshaping the narrative to downplay native Indian heroes.

"It is said that Jodha and Akbar got married and a film was also made on this story. History books also say the same thing but it is a lie," said Bagde.

What did Governor Bagde say?

Bagde specifically rejected the long-held belief that Akbar’s wife was a Rajput princess. He claimed that while the marriage was arranged by Raja Bharmal of Amer (in present-day Rajasthan), the bride was not a royal family member but the daughter of a maid in the royal palace.

To support this claim, Bagde pointed to the absence of any mention of “Jodha Bai” in Akbarnama, the official chronicle of Akbar’s reign written by his court historian Abul Fazl. Bagde implied that this omission weakens the commonly accepted narrative that Akbar married a Rajput princess for political alliance and religious harmony.

What do historians say?

According to most academic historians, Akbar married the daughter of Raja Bharmal of Amer in 1569 as part of a political alliance. She later came to be known as Mariam-uz-Zamani after giving birth to Jahangir, Akbar’s successor. In historical texts, she is also referred to as Harka Bai. The name “Jodha Bai” became popular much later, particularly through literature and cinema.

Scholars agree that there is no reference to “Jodha Bai” in Akbarnama. However, they argue that absence of the name doesn’t mean the woman Akbar married wasn’t of royal blood. Court chronicles often referred to royal women by titles or avoided naming them directly.

Why is this controversial?

Bagde’s remarks touch on two sensitive issues:

- Historical accuracy and colonial legacy

- The portrayal of Indian heroes and Muslim rulers in textbooks

He accused British historians of “deliberately altering” Indian history to glorify foreign rulers while sidelining resistance figures like Maharana Pratap and Shivaji Maharaj.

“The British changed the history of our heroes. They did not write it properly and their version of history was initially accepted,” Bagde said. “Indian historians followed them blindly.”

Bagde argued that the marriage story was an example of such distortion and called for greater scrutiny of established historical narratives.

What else did he say?

Bagde also challenged another accepted version of history—that Maharana Pratap, who resisted Mughal expansion in Rajasthan, ever wrote a treaty letter to Akbar. He said such claims are misleading and undermine Pratap’s legacy of uncompromising resistance.

“Maharana Pratap never compromised his self-respect,” Bagde declared. He expressed disapproval of the attention given to Akbar in school textbooks at the cost of Indian freedom fighters and resistance leaders.

He praised the National Education Policy (NEP) for introducing curriculum reforms aimed at restoring indigenous narratives and fostering patriotism.

New symbols of pride

Bagde highlighted the recent installation of an equestrian statue of Maharana Pratap in Sambhajinagar (formerly Aurangabad) in Maharashtra as a step toward recognising Indian warriors and their sacrifices.

He placed Maharana Pratap alongside Chhatrapati Shivaji as icons of Indian resistance who, in his view, could have “reshaped India’s destiny” had circumstances been different.

Governor Bagde’s claims have reignited the debate over India’s colonial-era historiography, especially the portrayal of Mughal-Rajput relations. While his statements are controversial, they reflect a broader movement to revisit and reinterpret historical narratives through a nationalist lens. Whether these claims hold up to scholarly scrutiny or not, they underline the growing demand to question long-held beliefs and reassess how history is taught and remembered in India.