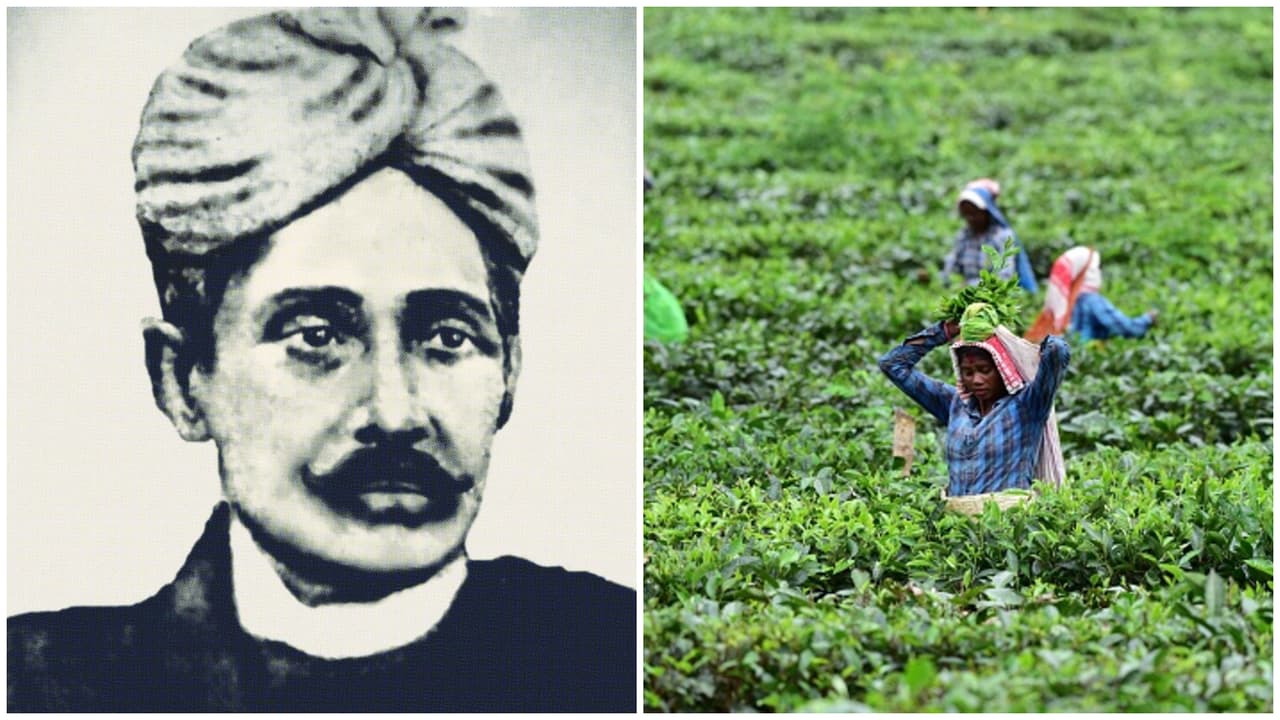

Though the British East India Company is often credited with popularizing tea in India, it was Maniram Datta Barua—later known as Maniram Dewan—who introduced the British to Indian-grown tea.

India is the undisputed nation of chai lovers. Today, on International Tea Day, let's pause to remember the man who sowed the seeds of India’s tea revolution—Maniram Dewan. While Indians pride themselves on their masala, green, ginger, and elaichi brews, the legacy of the visionary who dared to challenge an empire with a humble leaf remains largely unsung.

Though the British East India Company is often credited with popularizing tea in India, it was Maniram Datta Barua—later known as Maniram Dewan—who introduced the British to Indian-grown tea. Born in 1806 in Assam’s Jorhat district, Maniram played a pivotal role in revealing the tea-brewing traditions of the Singhpo tribe to British officer Robert Bruce.

Bruce, an agent of Ahom King Purandar Singha, had been seeking alternatives to costly Chinese tea amid the turbulent 1820s.

This quiet revolution culminated in Maniram becoming India’s first native tea planter. But his journey didn’t end with plantation success. Upon recognizing the British Empire’s exploitative intentions towards local growers, Maniram renounced his title of Dewan and courageously set up independent estates at Senglung and Cinnamara in the 1840s.

But unfortunately, the man who introduced a flourishing cash crop to the colonizers was hanged for treason on February 26, 1858. Ironically, he weaponized the very commodity he helped establish to weaken colonial control.

“Assam produced in Dewan a martyr to the cause of freedom of the country whose exploits are perhaps not yet well-known throughout India as they should be,” — Former Assam Chief Minister Bishnuram Medhi, in the foreword of K.N. Dutt’s Landmarks of the Freedom Struggle in Assam

Tea, Treachery, and Tyranny

Maniram hailed from a distinguished family that had migrated from Kannauj to Assam in the 16th century. During the Burmese invasion (1817–1826), the family sought refuge in Bengal. As the British seized control following the Anglo-Burmese War, Maniram forged a relationship with the colonizers, eventually becoming Tehsildar of Rangpur at just 22 under David Scott. His sharp intellect and influence earned him a place in the East India Company’s internal operations.

But it was his encounter with the Singhpo tribe of Upper Assam that changed history. As early as 1823, the tribe’s chief, Bessam Gam, personally demonstrated the ancient method of brewing tea in a bamboo hut. He opened a bamboo tube packed with sun-dried leaves, roasted in a metal pan days earlier, and infused them in hot water until the liquid glowed golden-orange.

Intrigued, Robert Bruce sent samples and seeds to Calcutta for verification. Their authenticity sparked a revolution—the formation of a Tea Committee in 1834. By 1838, Maniram was appointed Dewan of the Nazira estate in Sibsagar, solidifying Assam’s place as India’s tea capital, contributing over 50% of national production by 2019.

The Rebel Brewmaster

But prosperity came with a price. Dismayed by the British Empire’s exploitative practices, including unjust taxation and land seizure, Maniram resigned in protest. He harnessed his vast network of growers and his business acumen to open his own garden in Chenimore by 1844.

The British, alarmed by his rising influence, began viewing him as a threat. Undeterred, Maniram envisioned using tea not just as a commodity but as a catalyst for rebellion.

During the 1857 Revolt, he rallied support from Ahom royalty and the Assam Light Infantry, attempting to dethrone colonial control. Ahom leader Kandarpeswar even promised rewards to sepoys for reclaiming their homeland. However, the British foiled the plot, imprisoning Kandarpeswar in Calcutta’s Alipore Jail and sentencing Maniram to death.

He was executed the following year, leaving behind a trail of defiance and an indelible imprint on India's independence movement.

Legacy in Every Sip

Maniram Dewan’s legacy lives on—from the Maniram Dewan Trade Center, which hosts international tea festivals, to the national award-winning film Maniram Dewan (1963), celebrating his life and martyrdom. Yet his name still echoes faintly compared to the monumental role he played in both tea cultivation and India’s freedom struggle.

The next time you sip a comforting cup of chai, remember—it was once a revolutionary act.