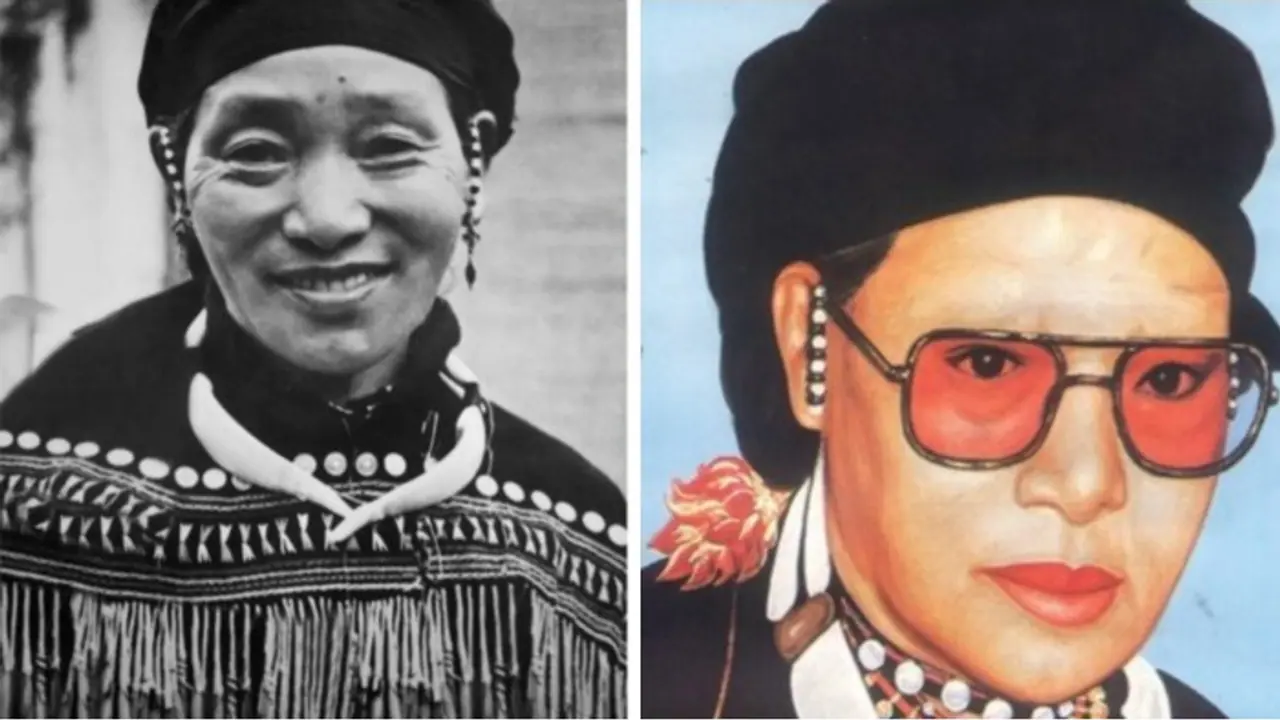

At just 13, Rani Gaidinliu of Manipur led a tribal rebellion against British rule, fought for cultural identity, and spent 14 years in prison. Her resistance remains a powerful legacy of indigenous pride and courage.

In the mist-covered hills of Hangrum, a remote village perched on the edge of Assam near the Manipur border, a teenage girl once evaded the British Empire with sheer grit and indigenous cunning.

This is the largely untold story of Rani Gaidinliu, a 13-year-old who led a tribal rebellion against colonial rule and spent 14 years imprisoned for her resistance.

Revered as a prophet by her people and feared as a revolutionary by the British, Gaidinliu remains a forgotten hero in India’s freedom movement.

A village of refuge and resistance

Hangrum's rugged beauty, jagged ridges, sweeping spurs, and cloud-laced mountains, provided the perfect battlefield and hideout. During the Hangrum War of 1932, this scenic village transformed into a stronghold for a growing tribal uprising led by Gaidinliu and her Zeliangrong followers. Secret tunnels, hidden exits, and fortress-like stockades gave her and her allies the tactical edge in their guerilla war against the colonial state.

Yet it wasn't just the geography that made Hangrum important! It was the spirit of resistance brewing under the leadership of a young girl.

From prophet’s disciple to tribal queen

Born in 1915 in Nungkao (now Luangkao) village in Manipur's Tamenglong district, Gaidinliu grew up without formal schooling but was deeply rooted in her tribe’s oral and spiritual traditions. At 13, she joined the Heraka movement — a socio-religious reform effort founded by her cousin, Haipou Jadonang, which aimed to revive indigenous Naga beliefs and resist forced Christian conversion and British taxation.

After Jadonang was executed by the British in 1931 on charges of sedition, the young Gaidinliu took over the mantle. She galvanized her people with a clear message: “We are free people; the white man should not rule over us.”

A tribal non-cooperation movement

Under her leadership, the Heraka movement evolved into a full-blown political resistance. Gaidinliu urged her people to reject colonial taxes, resist labour demands, and revive their indigenous religion centred on Tingkao Ragwang, the supreme creator. Like Gandhi’s call for non-cooperation, Gaidinliu's rebellion aimed to liberate her people from both political subjugation and cultural erasure.

But the British dismissed her as a “sorcerer” and viewed Heraka as a dangerous cult. In 1932, British troops launched an aggressive crackdown in Hangrum, culminating in a gunfight where tribal fighters armed with spears and arrows charged British sepoys.

Eventually, Gaidinliu went underground, retreating with her warriors to a fortified hideout in Pulomi village. But on 17 October 1932, she was captured in a surprise raid by Captain Macdonald. Marched to Kohima and later to Imphal, she was convicted for abetment of murder and sentenced to life imprisonment.

Rani of the hills

In 1937, Jawaharlal Nehru met the young prisoner in Shillong Jail. Moved by her courage, he dubbed her “The Rani of the Hills” and vowed to fight for her release. Though the British rejected multiple petitions, India’s independence in 1947 finally secured her freedom.

But Gaidinliu’s battle didn’t end there.

In post-independence India, she continued to advocate for a separate homeland for the Zeliangrong people, spread across Assam, Manipur, and Nagaland. Her stand often brought her into conflict with other Naga factions, forcing her underground once again in the 1960s. Yet, she kept engaging with Indian leaders, including Prime Ministers Indira Gandhi and Rajiv Gandhi, demanding tribal recognition and protection of indigenous culture.

Honours and forgotten promises

For her fierce resistance and unyielding activism, Rani Gaidinliu was awarded the Tamra Patra in 1972, the Padma Bhushan in 1982, and the Birsa Munda Award posthumously. India also honoured her with a postage stamp in 1996 and a commemorative coin in 2015.

Yet, many promises to preserve her memory remain unfulfilled. The Rani Gaidinliu Women’s Market in Tamenglong, inaugurated in 2018, still awaits its official opening, a symbol of the incomplete recognition of her contributions.

Legacy of resistance

Rani Gaidinliu died in 1993 at the age of 78, but her legacy lives on in the oral histories and cultural memory of the Zeliangrong people. To them, she was more than a freedom fighter. She was a prophet, a warrior, and a protector of their land and identity.

As Richard Kamei, a Zeliangrong scholar, reflects: “Her struggle is a message to India, and beyond, that the rights and interests of indigenous communities must be acknowledged and fulfilled.”

In a nation that celebrates many freedom fighters, the story of Rani Gaidinliu stands apart, not just because of her age or courage, but because she led a movement that was as much about preserving culture as it was about securing freedom.