NASA Study Shows Titan Breaks Chemistry Rule by Mixing Unexpected Molecules

Synopsis

Chalmers University scientists discovered that Titan’s icy surface allows polar and nonpolar molecules to mix — defying the “like dissolves like” rule. This rare chemistry could explain Titan’s alien landscapes and how life’s building blocks began.

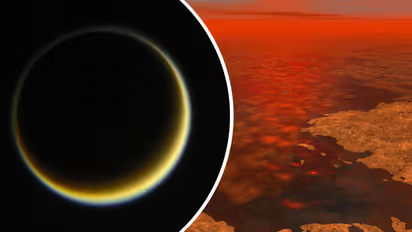

Scientists have long been fascinated by Titan, Saturn’s largest moon — a world of methane seas, icy dunes, and a dense orange atmosphere that might resemble early Earth. Now, a new discovery from Chalmers University of Technology and NASA has revealed that Titan is breaking one of chemistry’s most fundamental laws.

In Titan’s freezing environment, substances that should never mix — polar and nonpolar molecules — are forming stable crystals together. This violates the long-held rule of “like dissolves like,” which states that only similar molecules can combine.

The research, published in PNAS, could explain Titan’s mysterious surface chemistry and even hint at how life’s building blocks first formed billions of years ago.

The Chemistry No One Expected

At temperatures near –180°C, Titan’s surface hosts exotic chemistry that doesn’t happen anywhere else. Using lab experiments and computer simulations, the researchers showed that hydrogen cyanide (HCN) — a polar compound — can form co-crystals with nonpolar molecules like methane and ethane, both abundant on Titan.

“These are very exciting findings that help us understand Titan as a whole — a moon almost as large as Mercury,” said Martin Rahm, Associate Professor of Chemistry at Chalmers University and senior author of the study.

Normally, polar and nonpolar substances separate like oil and water. But under Titan’s ultra-cold conditions, the molecules arrange themselves into stable crystalline structures, defying conventional chemistry.

From a Simple Question to a NASA Collaboration

The discovery began with a mystery: what happens to hydrogen cyanide after it forms in Titan’s atmosphere? Does it simply pile up on the icy surface, or does it react with other chemicals?

To find out, NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) team cooled hydrogen cyanide, methane, and ethane to Titan-like temperatures and studied the mixtures with laser spectroscopy. The results were so strange that NASA reached out to Rahm’s group, experts in HCN chemistry.

Together, they ran massive computer simulations, testing thousands of molecular structures. The results confirmed that hydrocarbons can penetrate hydrogen cyanide crystals, creating new, stable materials that match NASA’s experimental data.

“It contradicts what every chemistry textbook teaches — that polar and nonpolar substances can’t mix,” said Rahm. “But under Titan’s extreme cold, the rules change.”

What This Means for Life and Planetary Science

The implications go far beyond Titan. Hydrogen cyanide is a key ingredient in forming amino acids and nucleobases — the molecular building blocks of proteins and DNA. If these strange co-crystals are common in the universe, they could help explain how prebiotic chemistry — the chemistry that leads to life — happens in icy environments across space.

“Our work gives new insight into how chemistry may have worked before life existed on Earth,” Rahm said. “And it shows how something as simple as temperature can rewrite the rules of molecular interaction.”

Looking Ahead: NASA’s Dragonfly Mission

NASA’s Dragonfly mission, scheduled to launch in 2028 and arrive at Titan in 2034, will investigate the moon’s surface and search for signs of prebiotic chemistry. Rahm and his team hope their findings will guide the mission’s experiments.

“Hydrogen cyanide is found everywhere — in comets, planetary atmospheres, and interstellar dust,” Rahm noted. “If Titan can host these mixed crystals, other cold worlds might, too.”

Until Dragonfly touches down, Titan remains one of the best laboratories in the Solar System for exploring how life might begin in the most unlikely places.