This Everyday Food Additive Could Affect a Child’s Health for Life

Synopsis

A study from Institut Pasteur found that food emulsifiers during pregnancy altered offspring gut bacteria, disrupting immune development and increasing lifelong risks of inflammation and obesity.

What mothers eat during pregnancy may have far reaching effects on their children’s health long after infancy. A new animal study suggests that widely used food emulsifiers, found in many processed foods, could quietly alter a child’s gut and immune system from the very beginning of life, increasing the risk of inflammation and obesity years later. The research was conducted by scientists at Institut Pasteur and published in Nature Communications.

How a Mother’s Diet Alters a Baby’s Gut

In the study, researchers fed female mice two common emulsifiers carboxymethyl cellulose (E466) and polysorbate 80 (E433) before pregnancy and throughout gestation and breastfeeding. These additives are frequently used to improve texture and shelf life in foods such as ice cream, baked goods, dairy products, and some powdered infant formulas.

Importantly, the offspring never consumed emulsifiers directly. Yet within weeks of birth, their gut microbiome had already changed. Because early life is a critical period when mothers naturally transfer beneficial bacteria to their young, these disruptions had lasting consequences.

When Immune Training Goes Wrong

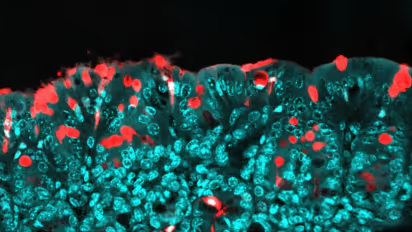

The altered gut microbiota in the young mice contained more flagellated bacteria microbes known to stimulate inflammation. Researchers also observed “bacterial encroachment,” where bacteria move closer to the gut lining than normal.

This early shift caused key gut pathways to close too soon. Under healthy conditions, these pathways allow small bacterial fragments to pass through the gut lining so the immune system can learn which microbes are harmless. When this training process is cut short, immune tolerance fails to develop properly.

As the mice matured, this breakdown in gut immune communication led to chronic low-grade inflammation. In adulthood, the animals showed a significantly higher risk of inflammatory bowel disease-like symptoms and obesity.

Why This Matters for Human Health

Although the research was conducted in mice, scientists say the findings raise important questions for humans especially during pregnancy and early infancy, when the gut microbiome is forming.

The results suggest that food additives may affect not only the people who consume them, but also the next generation. Researchers emphasize the need for clinical studies to examine how maternal diet, food additives, and infant formula may influence long-term health in children.

As ultra-processed foods become more common worldwide, understanding these hidden, intergenerational effects could reshape how food additives are regulated particularly in products designed for babies and expectant mothers.