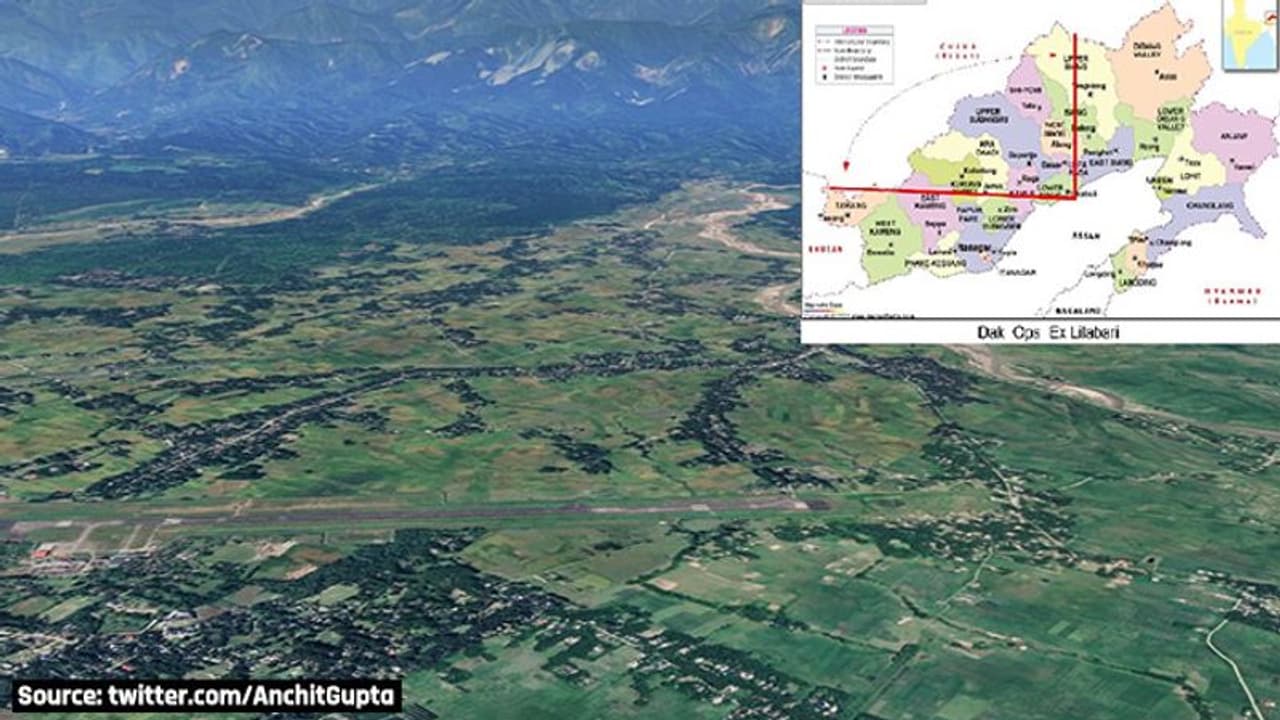

The small, desolate Lilabari airfield in the North Lakhimpur district of Assam lies nested deep in the North-East Frontier Agency (NEFA), but it has had a colourful aviation history with a deep link to the Indian Air Force, Kaling Airways, and Indian Airlines, says IAF historian Anchit Gupta.

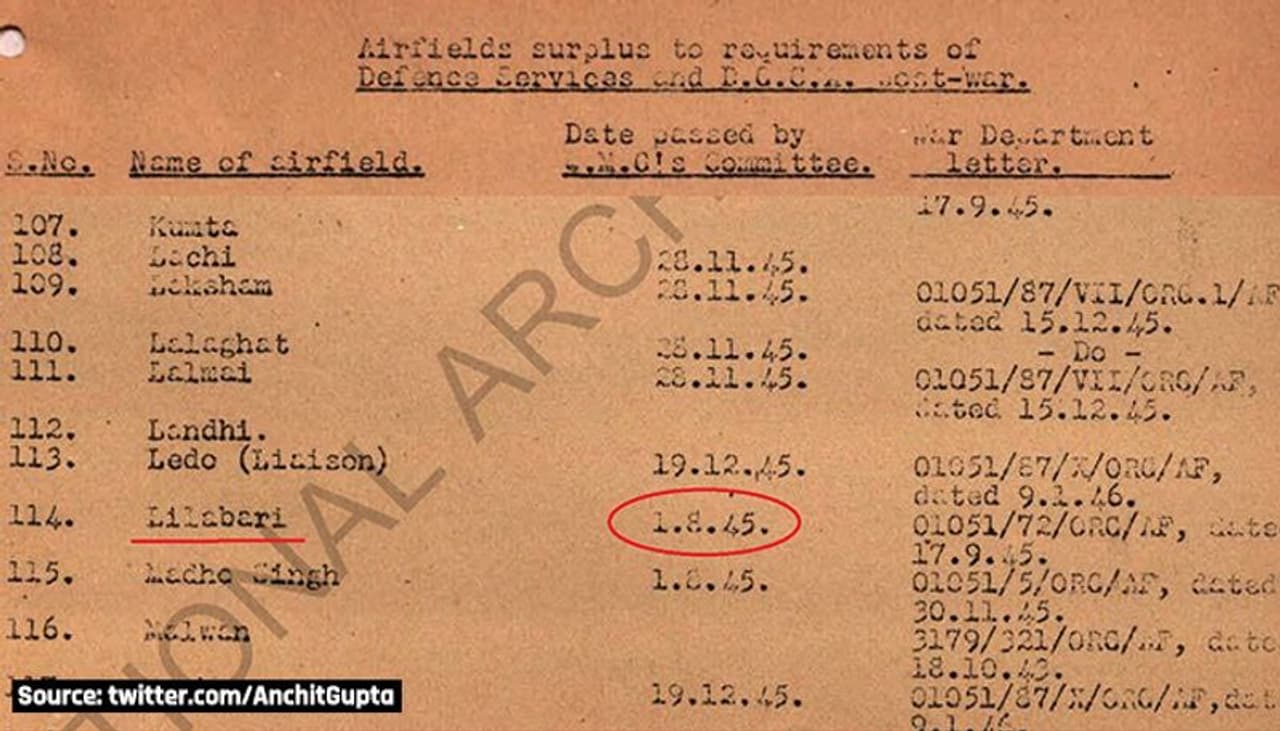

North East India was flush with airstrips (mostly 'kucha') made by the tea planters. These were later upgraded and used by the Air Forces (US/ Commonwealth) during the World War II Burma Operations. Post-war, most of these were declared surplus to military use, and even the Directorate General of Civil Aviation, Lilabari was no different.

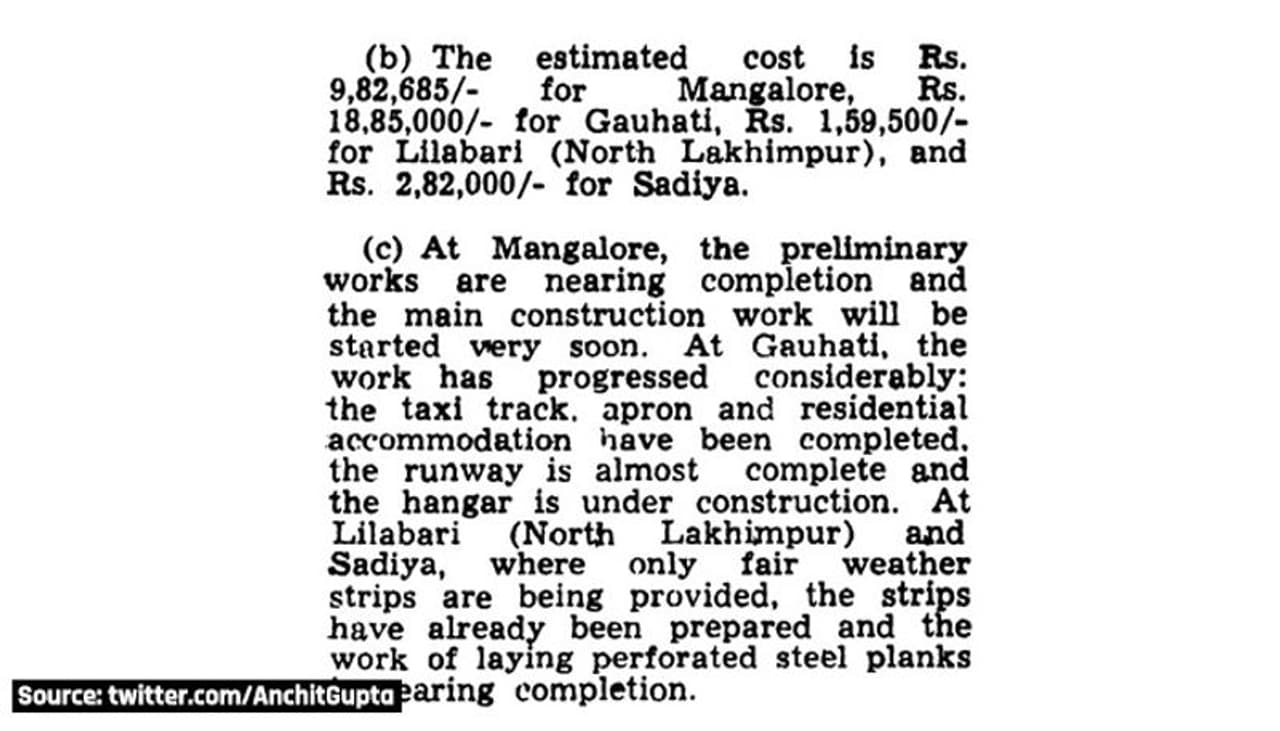

In 1951, the government decided to build airstrips in Assam and Lilabari was picked for a fair-weather strip. The airfield is located on a narrow strip of plain country lying between the Himalayas and the Brahmaputra, 8 km northeast of North Lakhimpur town at 101 metres above mean sea level.

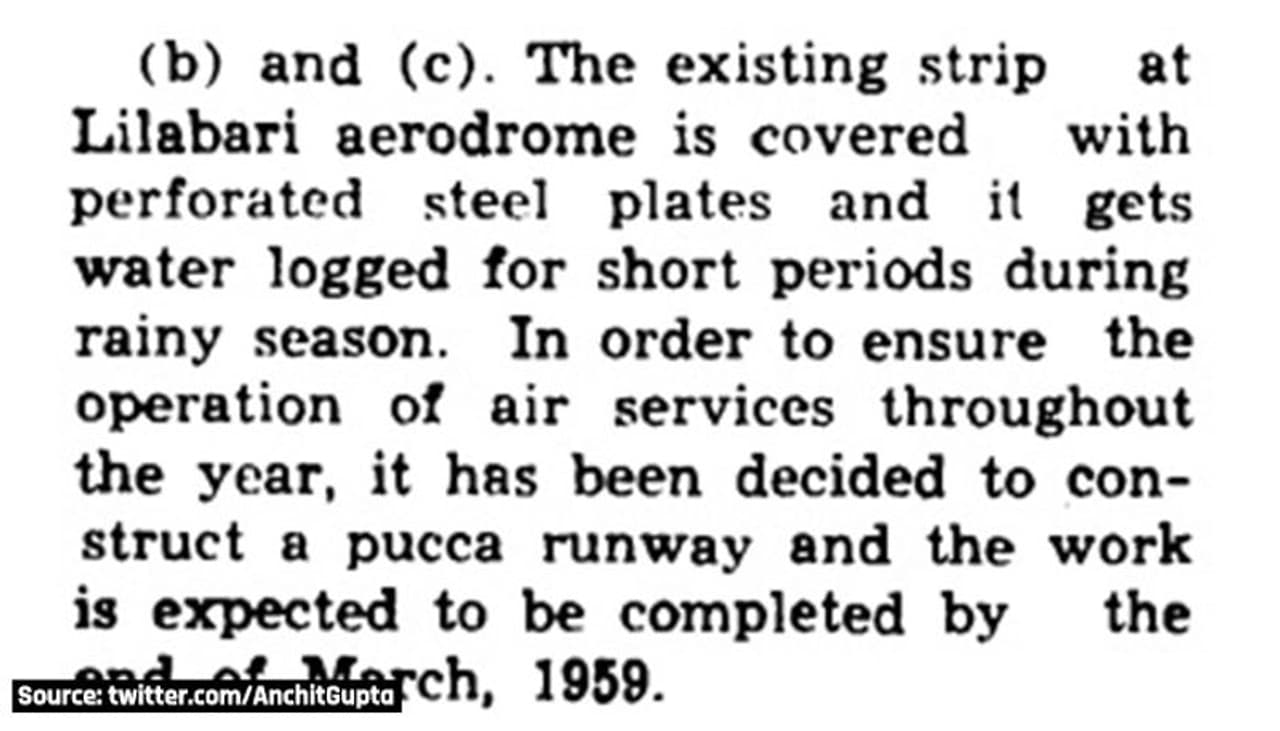

In 1953, Indian Airlines took it over, but flights were infrequent due to poor runway quality and bad weather. In 1958, the government undertook to construct a pucca runway, which only got completed in late 1960.

Militarisation of Arunachal (NEFA) meant Assam Rifles perforce had to be air maintained. Beginning with Rear Airfield Supply Organisation (RASO), unmanned Advanced Landing Grounds deep in NEFA (like Zero, Daparizo, Along, Tuting, Mehuka etc) and overhauling rail links north and south of the Brahmaputra.

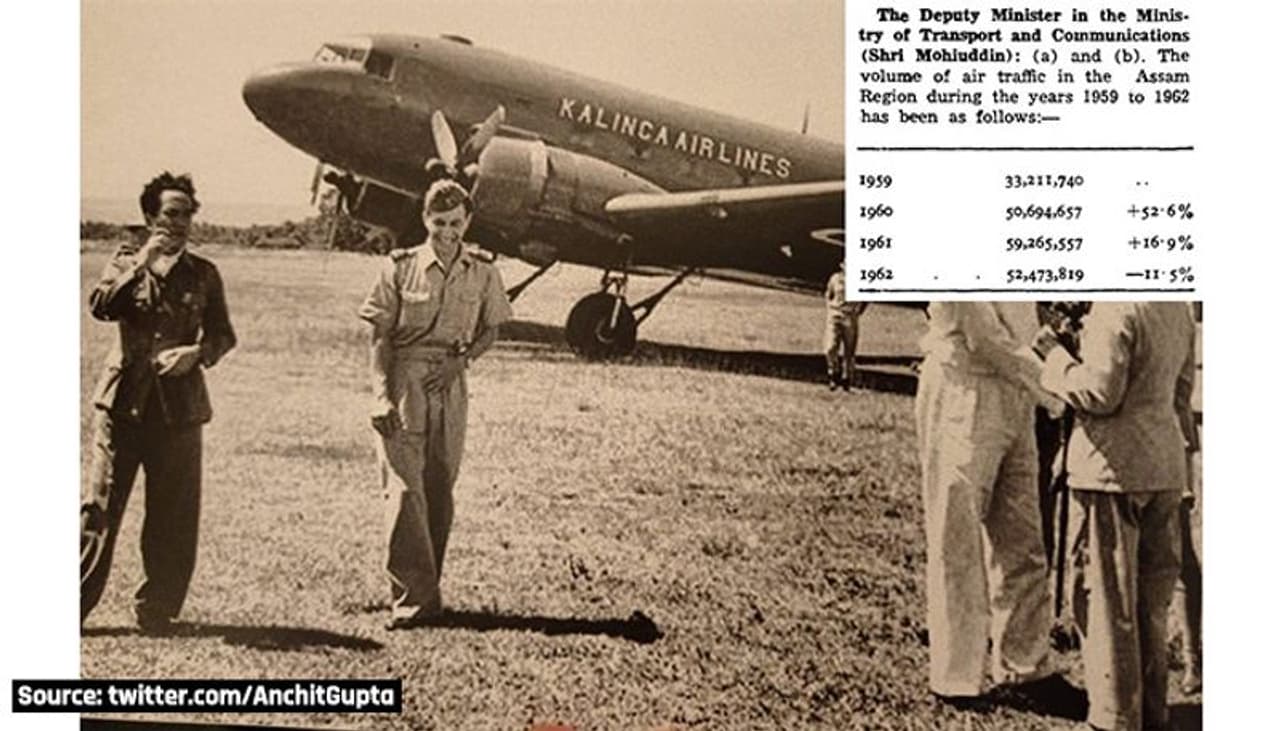

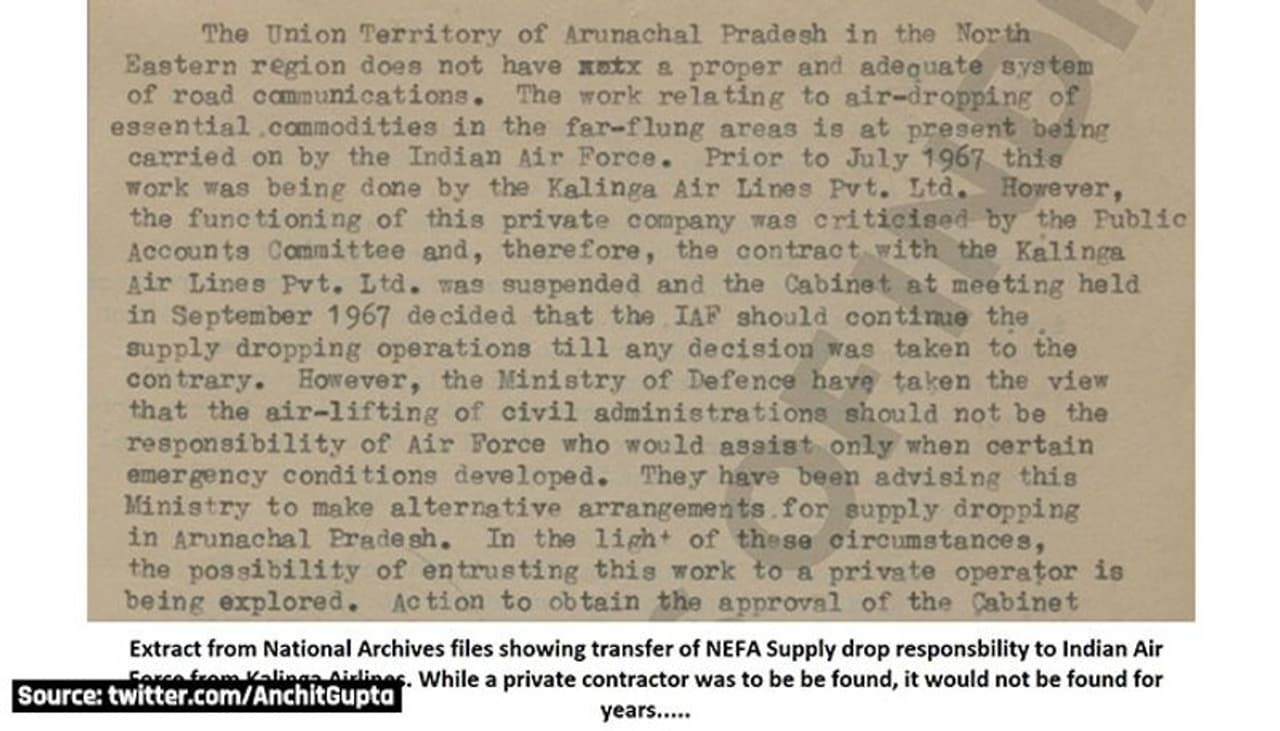

As the air maintenance effort increased, the government enlisted the support of Kalinga Airways in 1960 with a NEFA Supply drop contract for three to five years. In parallel, the IAF moved the 59 Squadron and the 49 Squadron to Jorhat to supplement the supply drop missions.

The 1962 war accentuated the need to build a superior air maintenance network. The IAF responded with bases along the Brahmaputra (south of it, except Tezpur). Bases were set up in Jorhat (1952), Tezpur (1959), Chabua (1962), Guwahati (1963) and Mohanbari (1964).

But two developments were going to lead to Lilabari for the IAF. The first was in 1965, when the administration created a new land-fed CPO at North Lakhimpur to support districts of Kameng, Subansiri and Siang, and the second was in 1966 when the DGCA made a new runway capable of taking load of all aircraft.

And amidst public pressure and heated arguments in Parliament about alleged favouritism towards Kalinga Airlines in giving them the NEFA contract, the government gave the entire job of NEFA supply drops to the Indian Air Force.

The Eastern Air Command Headquarters saw an opportunity to enhance the IAF's presence in NEFA. The HQ also advised the government to let the IAF run the operations from Lilabari, making it the only base significantly north of Brahmaputra. It moved the 43 Squadron, operating the Dakota, to Jorhat to exclusively manage this region.

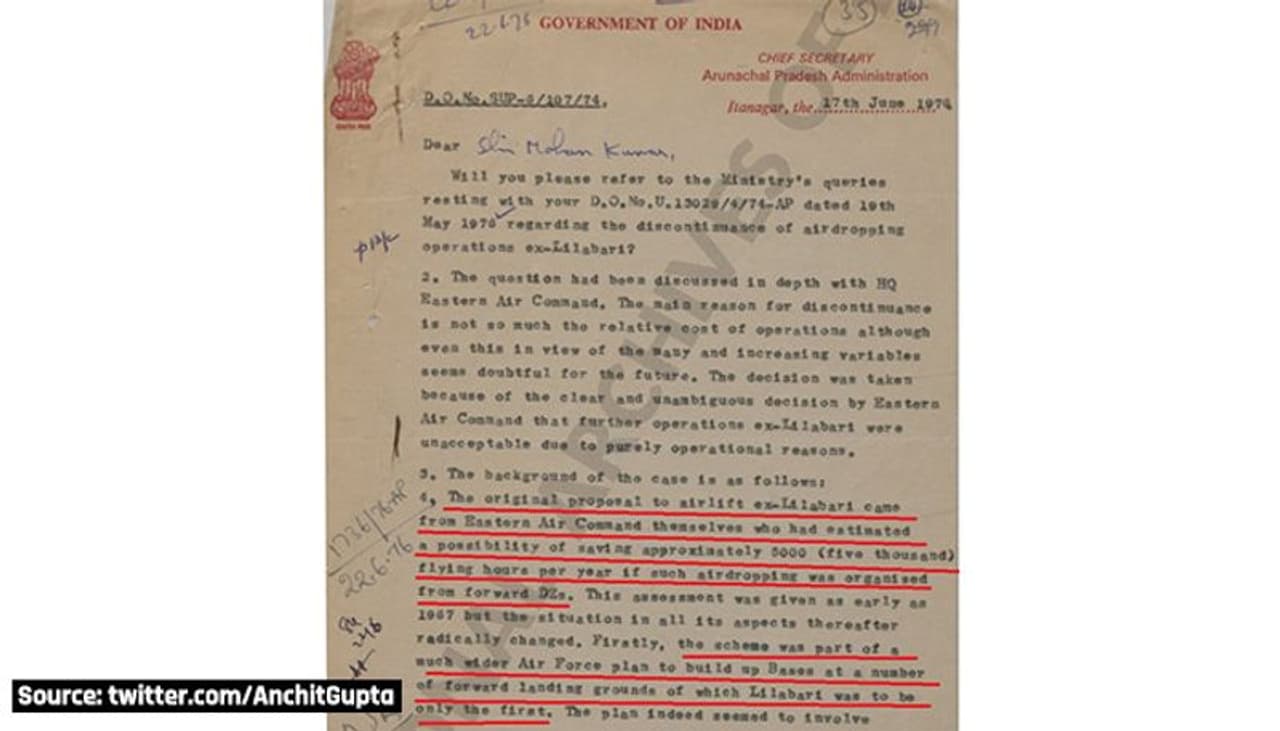

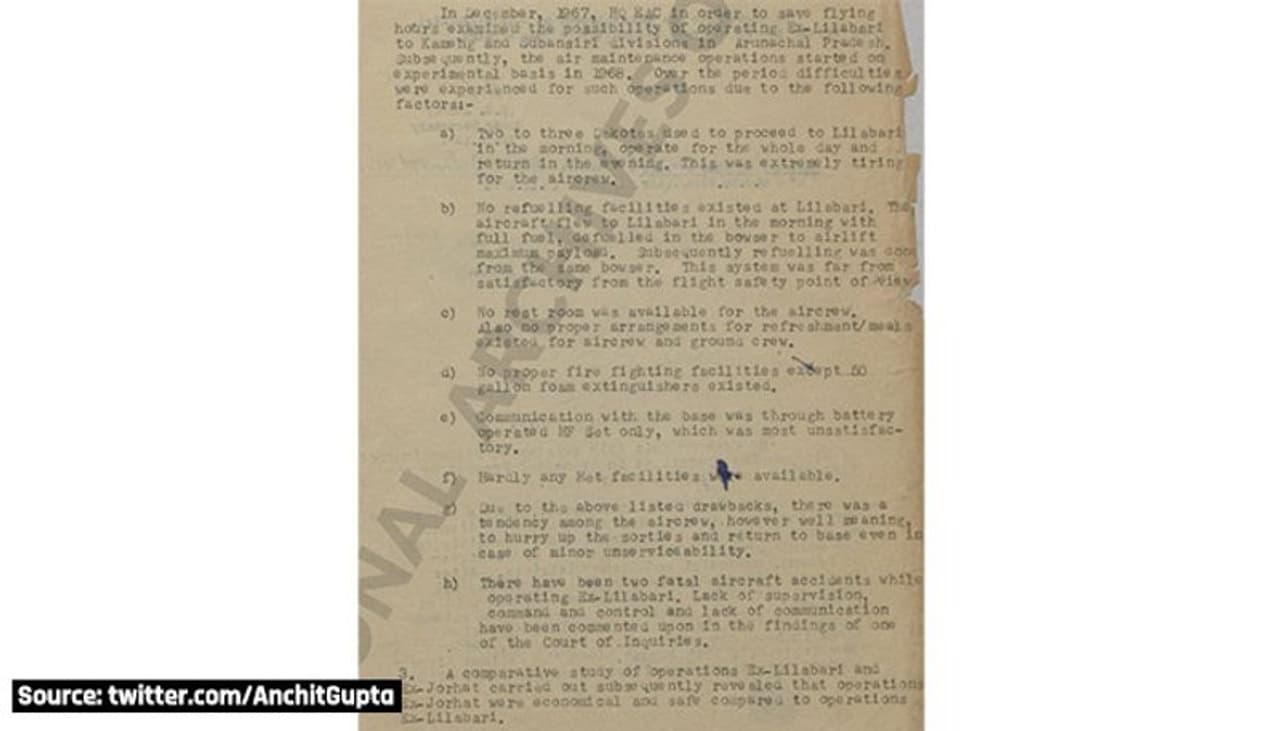

The Eastern Air Command believed that operating from Lilabari would save them 5,000 flying hours a year and help them expand the base network. Conversely, this came with administrative challenges due to the limited road connectivity to Lilabari to service the base.

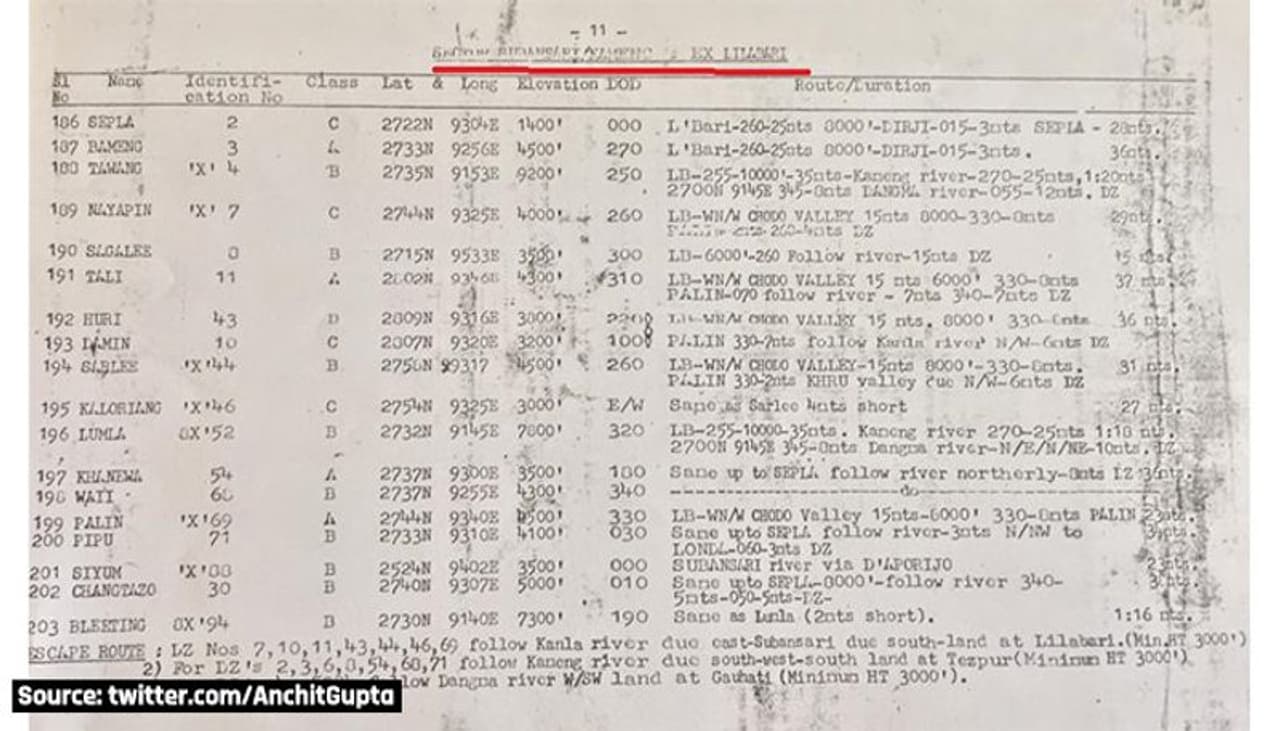

A simplistic demarcation was drawn. Demarcation zones to the west of Mechuka (districts of Tawang, West Kameng, East Kameng, Pakke Kesang, Paupum Pare, Kurung, Kra Dadi and Upper Subansari) were operated from Lilabari and to the east from Mohanbari with Jorhat as the permanent mother base to support operations.

Lilabari was then an 1800-meter tarmac runway with a hump, a civilian Air-Traffic Controller (one civil controller), a very high-frequency radio, a non-directional beacon, a small trailer-type fire trolley, and a civil terminal with no security. Lilabari had no Air Force personnel unless one took (a reluctant) ground crew along with them.

Parking at the airfield accommodated 3 aircraft. The crews set off from Johat around 4 am, carrying their breakfast and lunch. Each aircraft would launch up to five sorties and return to base. The IAF had positioned a static fuel bowser (without an engine) on the grassy tarmac.

The aircraft came with full fuel, parked with a wing over the bowser to de-fuel and fill it. After every trip into the hills, one refuelled, emptying the fuel which one had loaned to the bowser. The fuel load was measured using a calibrated dipstick, by climbing on the wing.

A sortie entailed up to 15 circuits. The door on the left side was removed. At the sill, the ejection crew stacked the gunny sacks weighing around 70 kg, or the containers with parachutes. On a red light, they would brace and on a green light, they would manually push these out.

Such tasks usually came with extant flight safety risks. At least two Dakota aircraft were fatally lost from Lilabari in the years to come. A Vayu Sena Medal (posthumous) citation to one of the crews of the 43 Squadron speaks volumes about the challenges faced.

In April 1975, the IAF suggested discontinuing the operations from Lilabari, choosing to revert to Jorhat. With the Dakotas on phase-out and operational and financial challenges in raising airbases, the IAF considered Lilabari a flight operation and safety challenge. But the actual withdrawal happened years later.

Project Vartak, launched by the Border Roads Organisation in 1960 has over the years improved the road network significantly and the need for air maintenance has come down considerably from those heady days of the 1950s-80s. Lilabari is now a regular civil aerodrome.

For the large number of IAF personnel and families who served in the North East during the 1960s-90s, the lasting memory of Lilabari is linked to the Fokker F-27 Service of Indian Airlines connecting Calcutta-Guahati-Tezpur-Jorhat-Lilabari-Mohanbari.

(The author weighed in on the knowledge and material of Wg Cdr Unni Kartha who was also a pilot with the 43 Squadron and operated out of Lilabari)